Decide Madrid

Madrid's Direct Democracy Experiment

Read Time

Brief View 4 MINS

Full Story 12 MINS

Briefing Notes

How Does It Work?

Decide Madrid is a citizen participation platform launched in 2015 that, amongst other features, allows members of the public to submit proposals to the City Council.

People wishing to make a proposal through the Decide Madrid website must first register by providing, as a minimum, their email address. Registered users can then create a “citizen proposal” of any length in text and/or video. Citizen proposals can be submitted via the website, by mail, or in person. To assist people in developing sound proposals, a resource kit and blog post with guidelines and tips are provided.

Once a proposal is submitted, any registered and verified resident of Madrid can click a button expressing support for a proposal. Once posted, each proposal is given twelve months to gather the public support needed for it to progress to the next phase of consideration. In order to advance to the next stage, a given proposal must receive the support of at least 1% of registered citizens in Madrid over 16 years of age (currently ~27,000 people) - this is a legal requirement that stems from Spanish law. If, after 12 months, a proposal does not reach this threshold, it is moved to the “archived” section of the website.

Proposals can be sorted by “most active,” “highest rated,” “newest,” and “archived,” or by category tags such as “culture,” “mobility,” and “social rights.”

To maximize citizen participation and accommodate those without internet access, most actions that take place on the website (including registration) can also be completed in one of Madrid’s 26 Citizen Assistance Offices with the help of trained staff.

If a proposal reaches the 1 percent threshold, a 45-day period of online public discussion is triggered. This period is followed by an additional seven-day period when verified users can vote to accept or reject the proposal. A majority vote in this process allows the proposal to move to the next stage - consideration by the City Council.

Any proposal that wins majority favor in the second round of public voting must be reviewed by the City Council within 30 days. During this 30 days, the Council evaluates the proposal based on its legality, feasibility, competence, and economic cost, all of which are set out in a subsequent report that is openly published. If the report is positive, a plan of action to carry out the proposal is subsequently written by City Council staff and published. If the report is negative, the City Council may either propose an alternative action, or publish the reasons that prevent the proposal’s execution.

What are the outcomes?

Decide is a mixed success. On the one hand, it offers an efficient mechanism for any member of the public to engage in democratic life and the free software that it utilizes is in use in 70+ cities. In Madrid, nearly 400,000 people are signed up and have submitted over 21,000 proposals. On the other hand, the legal requirement to obtain one percent of the population’s signatures (only two proposals have ever garnered the required support) before a proposal can move forward, combined with a number of design flaws, have resulted in thousands of proposals being submitted but none being enacted since the platform’s inception. Also many proposals put forth by citizens are poorly informed and designed in such a way that prevents their implementation, often because they are not under the jurisdiction of the City or they duplicate another law that already exists.The City of Madrid is seeking to test new ways to increase the number of signatures on citizen-submitted proposals while simultaneously improving their quality.

What does it cost?: The software is free and open source and developed by a community of volunteers. The City Council, however, pays for a staff member whose job is to focus on public engagement as his/her job.

What are the benefits?

- The clear and straightforward process make it easy to sign up and submit a proposal or vote on someone else’s.

- In-person citizen assistance venues ensure that everyone - regardless of their ability to access the internet - is included.

- Registration and verification ensure that only Madrilenians participate in certain processes.

- Even if the City Council cannot officially engage citizens on the platform, it can still see what people are talking about and care about.

What are the risks?

- The absence of a sample proposal or guiding questions means there is a lack of guidance as to what constitutes an actionable proposal, leading to lower quality submissions

- The inability of elected officials or staff to engage with citizen proposals means proposals that could otherwise have been developed into something implementable receive no feedback.

- The volume of proposals is very high, which limits participants’ ability to see many of them - as a result, many high quality proposals may go unnoticed.

Introduction

The City Council created the Decide Madrid civic technology platform in 2015 in response to the growing political disenchantment in Spain. Protests had begun years earlier when the Indignados (“outraged”) took to the streets of Madrid to demand better democracy, protest welfare cuts, corruption, and more. In the years following the massive protests, the champions behind the movement began to find their way into positions of power. Pablo Soto Bravo, a computer programmer turned City Council member led the development of the Consul software to create a way for ordinary people to participate in politics.[1] In use in over 70 cities, the Madrid version known as Decide enables a variety of forms of engagement, including participatory budgeting for which the city appropriates €100 million. Its consultations feature has been used to foster public discussion on 38 issues. The platform also includes a Propuestas (proposals) feature, which enables anyone to propose legislation. Decide enables a registered user to create a “citizen proposal” and a verified resident of Madrid to sign onto and support proposals for new regulations, policies or actions the submitter wishes the City Council to undertake. Proposals that receive enough signatures by residents must be considered by the City Council. There is, however, no obligation on the part of the Council to enact a proposal.

Decide is a mixed success. On the one hand, it offers an efficient mechanism for any member of the public to engage in democratic life. Nearly 400,000 people are signed up and have submitted over 21,000 proposals. On the other hand, the legal requirement to obtain one percent of the population’s signatures before a proposal can move forward, combined with a number of design flaws, have resulted in thousands of proposals being submitted but none enacted since the platform’s inception.[2] The City of Madrid is seeking to test ways to increase the number of signatures on citizen-submitted proposals while simultaneously improving their quality.

Propuestas Workflow

The goal of the proposals feature is to create a direct democratic process where citizens can submit, and subsequently support and vote on, one another’s ideas for new regulations, policies, and actions, for the City Council of Madrid’s consideration.

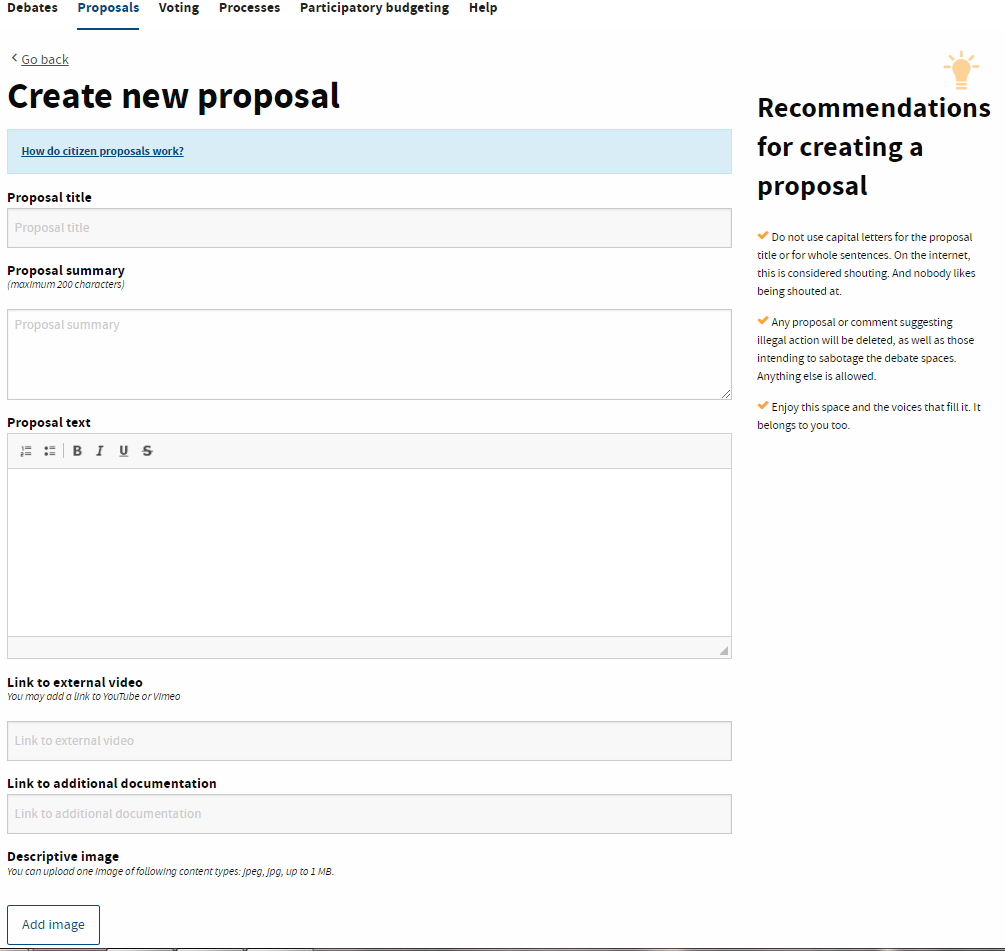

Figure 1: Screenshot from the “Propuestas” page. Source: decide.madrid.es

When creating a proposal, people can access “Kit.Decide” and a blog post via the Decide Madrid website, both of which offer guidelines and keys for creating a successful proposal.

Figure 2: Screenshots from the “Create a Proposal” page (auto-translated by Google). Source: decide.madrid.es

Registered users[3] can propose an idea by simply clicking the “Create a Proposal” button. To register only requires providing an email address. There is no residency requirement to make a proposal, and they can also be submitted by mail or in person. A proposal is comprised of:

- Title

- Summary (max 200 characters

- Proposal text (no limit)

- Link to external video

- Link to additional documentation

- Descriptive image

- Additional documents (max of 3, must be PDFs)

- Scope of operation (select a neighborhood or entire city)

- Place marker on map to represent scope (if applicable)

- Tags

- Full name of person submitting proposal (not displayed publicly)

Over 21,000 proposals have been submitted and are available to view on the site, sorted by “most active,” “highest rated,” “newest,” and “archived” (can no longer receive support), or by tags such as culture, mobility, and social rights.

Over 21,000 proposals have been submitted and are available to view on the site, sorted by “most active,” “highest rated,” “newest,” and “archived” (can no longer receive support), or by tags such as culture, mobility, and social rights.

Once a proposal is submitted, anyone with verified accounts can click a button expressing their support for said proposal.[4] Each proposal is given twelve months to gather requisite support (signatures) to advance in the process. Some examples of active proposals with a high number of signatures include a protest against a trash incinerator and a moratorium on tourism in the Madrid town center, with 5,225 and 2,427 signatures, respectively. To move forward for consideration, a proposal must receive the requisite support, represented by signatures from “one percent of registered citizens in Madrid over 16 years of age” which is currently ~27,000 people (Decide Madrid).[5] If a proposal does not reach this threshold, it is moved to the “archived” section after 12 months.

If a proposal receives the required number of signatures, this triggers a 45-day period of deliberation and discussion by the public on the website, where they can get informed about the topic of the proposal. Afterward begins a seven-day period (final voting phase) when verified users over 16 years of age can again vote to accept or reject the proposal. A majority vote in this process decides whether the proposal is brought to the City Council for consideration. There is no minimum requirement for consideration at this stage.

The City Council must review any proposal that wins majority favor in the final voting phase within 30 days. It should be noted that winning proposals are not automatically implemented, as the Spanish Constitution does not permit such binding referenda. During this 30 days, the Council evaluates the proposal based on its legality, feasibility, competence, and economic cost, all of which are highlighted in a subsequent report that is openly published. If the report is positive, then a plan of action will be written and published to carry out the proposal. If the report is negative, the City Council may either propose an alternative action or publish the reasons that prevent the proposal’s execution.

Participation

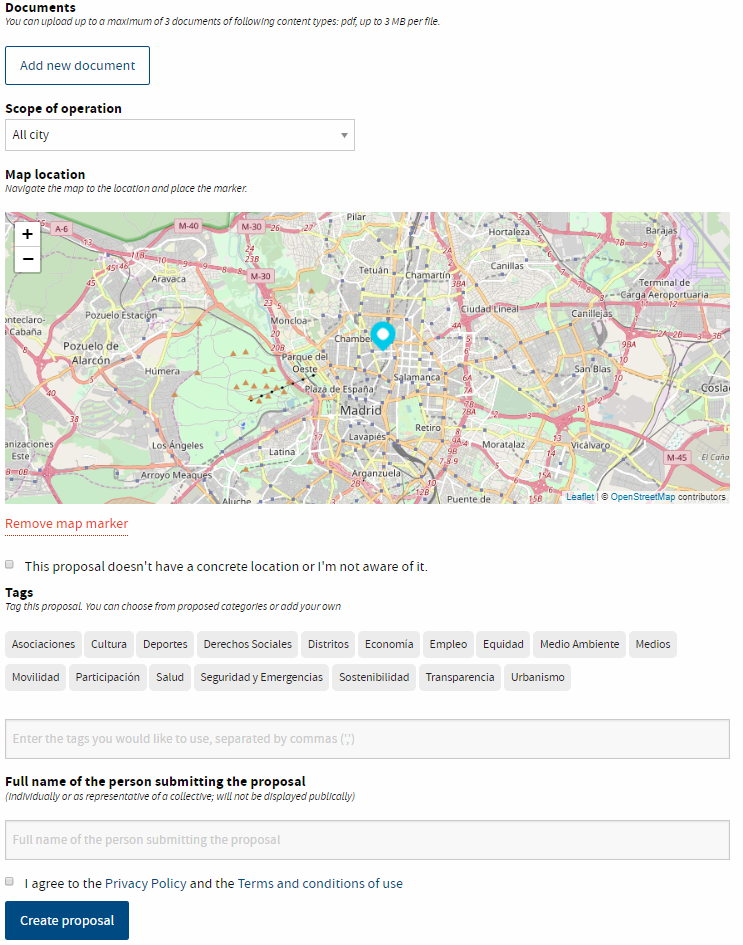

The Decide Madrid website provides a general overview of user statistics, but the information provided is not available in one centralized and easily accessible location. Rather, it is scattered across the website on different pages. However, the site does provide a link to the Madrid City Council’s “Open Data” portal, where one can find a substantial amount of data on Decide Madrid through a downloadable application programming interface.[6] Site traffic and user participation are the areas where the platform has found great success, demonstrated by the below statistics provided by ParticipaLab.[7]

Figure 3: User data as of May 04, 2018. Source: Yago Abati, Director - Laboratorio Inteligencia colectiva para la Democracia (ParticipaLab)

Unfortunately, the site does not provide more specific data on user behavior and activity, such as the amount of time the average user spends on the site, the number of frequent users, the number of votes cast or proposals submitted by the average user, location, occupation, etc. While some of that information is likely protected by privacy laws, more data and a deeper understanding of the platform’s users would help Decide Madrid administrators, and those who wish to replicate the process, identify challenges with using such a tool and potential solutions. However, some of this information can be found with some searching on ParticipaLab’s “ now defunct Data Analysis for Citizen Participation” site, though it requires significant manual effort. In addition, the website does offer an extensive overview of data from one week in February 2017, when the City Council combined the opportunity to vote on two citizen proposals and several “processes.” If such data were collected pertaining to the entire site, it would be highly valuable.

February 2017 Voting

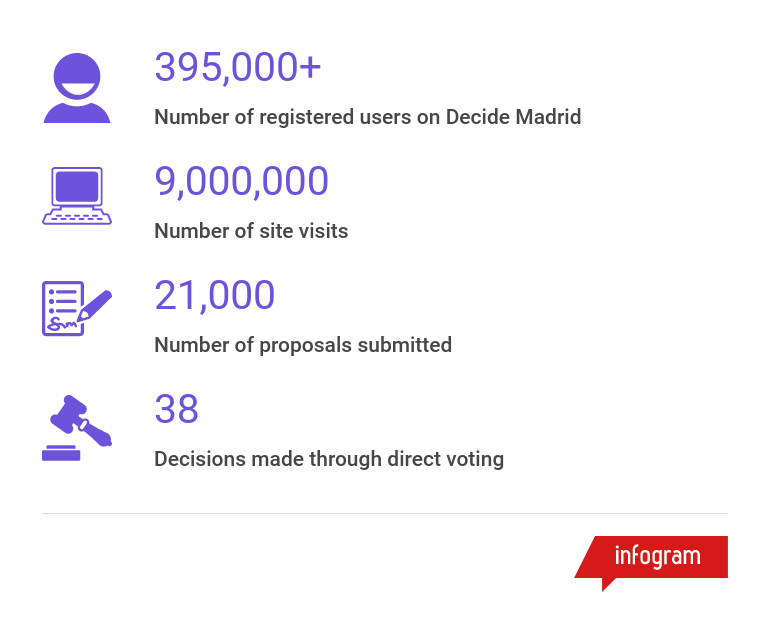

Due to a coincidence in how the timing unfolded, the City Council combined the opportunity to vote on two citizen proposals and several “processes”, into one week in February, 2017 where citizens could vote on all of these different items. This “first citizen vote” provides the richest set of user data available on the site, thus the following figures and statistics all pertain to that vote. Of particular note is the number of people participating via the mail, rather than the web.

- Number of users who voted: 217,076

- Number of votes cast: 963,887

- Participation by Gender:

- Men: 105,298 (49.23 percent)

- Women: 108,591 (50.77 percent)

- Participation by Channel:

- Web: 76,481 (35.73 percent)

- Ballet box: 23,654 (11.05 percent)

- Mail: 117,388 (54.83 percent)

Below is a graphic representing votes by age group. For more detailed information about participation broken down by geography and subjects of the votes, please visit First Citizen Vote (February 2017):

Figure 4: Votes by age group. Source First Citizen Vote (February 2017)

Risks and Challenges

Undoubtedly, the most obstinate challenge faced by Decide Madrid is advancing citizen proposals through the process to be passed into legislation because of the signature threshold. Despite impressive participation numbers with nearly 400,000 registered users and over 21,000 submitted proposals, since the platform’s inception in 2015, only two of these proposals have reached the threshold of signatures required for them to be put to a vote for consideration by the Council. Notably, both of these proposals were submitted on the day the platform was launched, and in the subsequent months not one single proposal has reached even half of the support threshold.[8]Equally problematical, however, is the quality of proposals. Many submissions are poorly informed and designed in such a way that prevents their implementation because the City government is not permitted to respond to or give feedback on proposals.

Equally problematical, however, is the quality of proposals. Many submissions are poorly informed and designed in such a way that prevents their implementation because the City government is not permitted to respond to or give feedback on proposals.

Thus, many are not relevant to the jurisdiction of the City or they duplicate another law that already exists. In other words, many proposals with credible ideas that offer practical solutions to real problems are drowned out by the volume of ineffectual proposals.

This poses a delicate issue. One of the goals of such participatory democracy tools is to enable wider participation. In doing so, however, Decide Madrid has attracted a surfeit of contributions that are proving ineffective to the initiative’s broader vision of improving the city’s democracy and the lives of its citizens. Additionally, if its users’ contributions continuously fail to produce outcomes, then they may get discouraged. Thus, administrators must discover a way to invite more useful proposals and mitigate ‘noise’ without limiting overall engagement.

Key Learnings

Decide Madrid provides several learnings for governments and institutions that look to emulate its CrowdLaw processes. Giving the public the opportunity to influence law and policymaking directly is responding to a deeply felt need as evidenced by the huge number of participants and submissions.

Giving the public the opportunity to influence law and policymaking directly is responding to a deeply felt need as evidenced by the huge number of participants and submissions.

However, the failure by the government -- a failure created by legal compliance -- to participate actively in and respond to public proposals is depressing the quality of submissions,

Finally, the case of Decide Madrid highlights the importance of technology in these processes. Above all, using open source software is a core value when designing a digital democracy platform. When asked about the Consul software, Miguel Arana, Director of Citizen Participation for the City Council of Madrid, remarked "This is the tool we imagined when we started doing digital democracy practices in the squares and streets of 15M."[9] He continued to explain how he believes that “free software is always a gift to the world.” The influence of free software is well-supported,[10] and Decide Madrid’s Co-founders are proud that their vision was able to be reimagined in the many instances that followed.

Impact

Overall, Decide Madrid has been very successful on some fronts but has fallen short of producing substantial tangible impacts in other areas. Madrid’s City Council has succeeded in creating an open, transparent platform where citizens can collaborate with one another on a range of issues. Placing every part of the process in full view of the public and providing a link to an open data repository has helped meet the goal of promoting transparency within the government. Engaging hundreds of thousands of citizens, Decide Madrid has moved over 500 participatory budgeting projects into the process of being implemented and crowdsourced opinions to make nearly 40 decisions through the “process” section.

Unfortunately, the extremely low impact of the propuestas (proposals) feature--the aspect that has the most direct influence on the solution identification stage of the lawmaking process--is cause for relative concern. Furthermore, the political climate in Spain remains turbulent as trust in government continues to decline and there is a real concern that a lack of outcomes will lead to further frustration.

Conclusion

Whether Decide Madrid has enabled citizens to directly influence the City’s policies and leverage citizen participation for solution identification currently lies in a grey area. While the platform has granted citizens with the ability to identify and propose alternative solutions to public problems directly to the City Council, their capacity to prompt real change remains questionable as long as citizen proposals continue to produce very few substantive results. On a positive note, the organizers have been mapping and tracking user data and participation, and are eagerly working on improving the process to help accomplish its goal. They have set the foundation for their government to work collaboratively with the public and civil societies, and have done so in a way that is replicable for other institutions.

Footnotes

[1] De Sousa, Ana Naomi. “Hacking Madrid.” Al Jazeera, Dec. 13 2015.

[2] One proposal was “Billete único para el transporte público,” which called for citizens to be able to purchase one universal ticket to access every form of public transportation. The other proposal was “Madrid -- 100% Sostenible,” a self-proclaimed manifesto which demanded the implementation of 14 points related to sustainability.

[3] There are three levels of authentication for the site. Registered users provide a username, email address, and password but do not verify residence, so people can do this from anywhere in the world. Basic verified users verify residence online by entering their residence data, then receive a confirmation code via mobile phone. Users who wish to become completely verified will receive a letter containing a security code and instructions to carry out the verification, which they must send back to a Citizen Assistance Office.

[4] Note: in order to maximize citizen participation and accommodate those without internet access, most actions that take place on the website (including registration and verification) can also be done in one of Madrid’s 26 Citizen Assistance Offices with the help of trained staff.

[5] While it is not clear whether there is a legal reasoning behind the 1% threshold, it is possible that it may stem from Article 187, Section 2 in “Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General,” which explains the scale for the required number of signatures to present candidacy according to the size of the given Spanish municipality.

[6] “Portal de datos abiertos del Ayuntamiento de Madrid.” Ayuntamiento de Madrid.

[7] Yago Bermejo Abati, Director - Laboratorio Inteligencia colectiva para la Democracia (ParticipaLab) personal communication, May 04, 2018.

[8] Pablo Aragon, Yago Bermejo, Vicenc Gomez, and Andreas Kaltenbrunner. “Interactive Discovery System for Direct Democracy." 2018 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM). IEEE, 2018.

[9] Tarancón, Sara Calvo. “La hacker de Carmena.” Público, Jan. 14 2018.

[10] “What is free software.” Free Software Foundation.