Constitución CDMX

Crowdsourcing Mexico City’s Constitution

Read Time

Brief View 5 MINS

Full Story 16 MINS

Briefing Notes

How Does It Work?:

Mexico’s Congress gave the Mayor of Mexico City exclusive authority to craft the city’s constitution, which would then be ratified by a constitutional assembly. However, to increase popular legitimacy, the Mayor, instead, established a working group tasked with receiving public input. The Lab for Mexico City set up the Constitución CDMX (CDMX referring to “Ciudad de México”) digital platform, which offered the public four ways to participate in the process: 1) a survey, 2) online petitions, 3) collaborative drafting, and 4) an event register. The opportunities to participate were heavily advertised via social media and local high school volunteers were enlisted to get out the word on street corners.

1) Survey: This seven question survey aimed to capture residents’ hopes and fears, expectations, and ideas for the future of the city and mapped them by age, gender and neighborhood.

2) Online Petitions: The City collaborated with Change.org Mexico to set up a tool where residents could petition the working group. Any petition with 5,000 signatures was analyzed and a legal opinion was sent to the petition-maker and its signees. When a petition garnered 10,000 signatures, the proposing resident(s) would present their proposal to three representatives of the Working Group. When a petition surpassed 50,000 signatures, the proposing resident(s) presented their proposal in a working session with the Mayor, who committed to explicitly include it in the constitutional draft.

3) Collaborative Drafting: Residents could add their coments or suggestions to essays prepared by the Working Group that addressed questions of constitutional theory, proposals of a technical nature, and related academic papers using mMIT’s pubpub platform.

4) Event Platform: An event platform was created that enabled resident-organized events related to the constitution to be promoted to increase participation. Event organizers could also upload the findings of their events to the collaborative editing platform and receive feedback from other platform users.

Each week, the Working Group reviewed a summary of the Constitución CDMX platform’s activity, discussed the resident inputs and, with technical and legal support, reflected the result of their discussion in an evolving draft of the constitution. The Working Group’s final draft was then passed through the Mayor to the Constitutional Assembly which held responsibility for final review and endorsement of the constitution.

What are the outcomes?: Within six months, 341 proposals were submitted as online petitions, and signed by more than 400,000 unique users. Four petitions surpassed the 50,000 signatures threshold, while another 11 got more than 10,000 signatures. In total, 14 petitions were successfully included in the Constitutional draft . Additionally, the survey mechanism generated 30,000 geo-tagged responses from 1,474 neighborhoods, accounting for 90% of all neighborhoods in Mexico City; 100 essays were submitted to the collaborative drafting platform and received 1000 comments; and 55 resident-organized events were registered. As a result, the final document is considered to be the most progressive constitution in Latin America, and it has been recognized by the United Nations as a “historical document that addresses the central challenges of development and peace” and as “a guide to fulfill the universal, indivisible and progressive nature of human rights, the Sustainable Development Goals, and the 2030 Agenda.”

What does it cost?

The platform development cost was $15,000. There were also additional costs for outreach and marketing, as well as digital kiosks and mobile devices which were used to encourage participation from citizens who did not have access to the Constitución CDMX platform online.

What are the benefits?

- Having multiple ways to participate - from filling out a survey to writing a petition - encouraged more people to participate.

- The Mayor’s commitment to include language drafted by the public if it garnered enough signatures enhanced legitimacy. At the same time, the Mayor made clear that citizen proposals that did not reach the signature threshold would be considered but not automatically included. By clearly communicating these boundaries, expectations were surpassed.

- Partnership with a well-known brand name (Change.org) increased trust and participation in the process.

What are the risks?

- The main challenge initially encountered was the lack of trust in the process and with the government - trust was essential to robust citizen participation.

- The still-present digital divide in Mexico City created implementation challenges and necessitated offering face-to-face participation options.

Background

Earning the same rights and liberties as other states in the Mexican Republic had been a long fought social and political battle of Mexico’s capital city. Twenty years after the first mayoral election – the President used to appoint the city’s mayor – the creation of the first local constitution was supposed to be another milestone in the city’s democratization process. But a complex local political scenario and a nationwide distrust in government raised questions about the real utility of a new constitution for the continent’s biggest city.

Mexicans’ trust in government and, more troubling, satisfaction with democracy, is at historic lows. According to the Pew Research Center, a mere 2% of the Mexican population trust their government and only 6% of Mexicans are satisfied with the democratic system itself. These levels of dissatisfaction are below any other regional or international comparisons.

Against this backdrop, when the National Congress designed a process for the creation of the city’s first constitution which did not contemplate public engagement, it threatened the legitimacy of the occasion. Instead, they granted the Mayor of Mexico City the exclusive authority to create the draft of the constitution, which would then be voted on by members of a Constitutional Assembly (40% appointed by other government branches and 60% democratically elected). But no popular participation was contemplated despite the fact that the new constitution would lay the groundwork for all other legal and institutional reforms to follow.

Historically, Mexico City’s laws and institutions, especially regarding public security and budgetary affairs, had to have the Federal authorities’ approval. However, its new legal status granted the capital city more autonomy. Thus, following the enactment of a new constitution, a complete overhaul of existing laws would need to follow. Any lack of legitimacy of the original process could have called into question the legitimacy of these subsequent enactments and negatively impacted people’s hopes and expectations for the city’s future.

Given this starting point, Mexico City had to come up with creative ways to innovate and recover the population’s trust in the constitutional process, while imagining new ways of communicating the importance of the new constitution in daily life. By using accessible yet substantive mechanisms, the city’s adoption of crowdlaw practices -- enabling ordinary citizens to participate -- would transform this fraught process into a more legitimate and effective one.

Mechanics of Constitución CDMX

In order to open up the constitutive process, the Mayor established a Working Group (WG), comprised of 30 leading citizens from different spheres of city life. Among the members of this group were activists, poets, artists, Olympians, constitutional experts, and deans and academic authorities of national universities. Parallel to this, the Mayor instructed Laboratorio para la Ciudad– Mexico City’s creativity and experimentation office– to develop a methodology and platform to channel popular opinions and proposals made for the Constitution to this working group.

The Mayor committed not to veto or modify any draft made by the Working Group without the platform’s input.

The Lab for Mexico City hired a small civic tech startup at the cost of $15,000, to build a digital platform to facilitate public input. Staff at Laboratorio para la Ciudad and Mexico City’s General Counsel Office, who collaborated during the six-month period the platform remained active, jointly managed the process.

The challenge was to design a platform versatile enough to fully comply with the Mayor’s commitment to integrate into the constitution all opinions and proposals generated by the people, regardless of the user’s knowledge of constitutional affairs, their academic background, or level of interest in public affairs.

Figure 1: Constitución CDMX digital platform.

The platform offered four different options for the user to participate, depending on their interest in the matter, time availability, and level of knowledge about specific affairs and used Change.org and volunteers from Mexico City’s public high schools, who promoted offline participation in public spaces, as two mechanisms for spreading the word about the opportunity to participate.

One participatory mechanism was the survey Imagina tu Ciudad, designed to elicit the citizen’s hopes and fears, expectations, challenges, and ideas for the future of the city. Through a seven question survey, the government aimed to obtain information on a general level about the people’s hopes and expectations for the future of the city, the main challenges they identified, as well as its most valuable assets. This mechanism led to 31,000 geo-tagged submissions. This survey allowed the user and the government to navigate – by neighborhood, age, and gender – citizens’ gravest concerns and their visions for the future.

Another way to interact with the platform was to draft an online petition via Change.org. Mexico City’s Government became the first Mexican authority to commit to specific actions depending on the number of signatures the petition would gather. Any petition to obtain 5,000 signatures received a formal legal analysis by the city with that legal opinion sent to the petition-maker and signees. With 10,000 signatures, the citizen got to present their proposal to three representatives of the Working Group. Those whose petitions surpassed a 50,000 signature threshold presented their petitions in a working session with the Mayor, who committed to explicitly include them in the constitutional draft to be debated and discussed. Within six months 341 proposals were submitted as online petitions, and signed by more than 400,000 unique users.[1] Four petitions surpassed the 50,000 signatures threshold, while another 11 got more than 10,000 signatures. In total, 14 petitions were successfully included in the Constitutional draft.

The third mechanism was another collaborative drafting platform but this one gave people the chance to annotate and comment on essays written by the members of the Working Group dealing with constitutional theory, technical proposals, and academic papers. This platform was based on MIT Media Lab’s PubPub, which was used for policy making and public affairs by Mexico City in previous exercises. This mechanism allowed citizens to enrich published essays with commentaries and suggestions and open up discussions over specific contents of the text they deemed relevant.

Annotation platforms might present themselves as the most obvious mechanism to engage in a Crowdlaw initiative. However, the team that implemented Constitución CDMX faced many challenges when trying to get people to engage in the discussion through it. It was the least popular participatory mechanism for the Mexico City exercise, due to the complexity of the texts it contained, and its unapproachability by a general audience.

The fourth mechanism of Constitución CDMX allowed citizens to register any event they organized related to the Constitution. Additionally, organizers could upload their event’s ideas and recommendations to the collaborative drafting platform and receive feedback from other users.

Figure 2: “How to participate?”. The platform hosted four different tools for

civic

engagement,

and an external link to the local Electoral Institute’s webpage.

Source:

Constitución CDMX digital platform.

Each week, the managing team would present to the working group a summary of the platform’s activity, including petitions’ growth, new answers to the survey, as well as a summary of the registered events and collaborative essays. These inputs were discussed by the Group in its weekly meetings and integrated into the texts that would eventually become the city’s first constitution.

Crowd Constitutionmaking in Action

Patricio, a 16-year old high school student, lives in Magdalena Contreras, a borough in the southwestern outskirts of Mexico City proper. Waters from the surrounding mountains descend to the Valley of Mexico through this borough. Being a daily witness to the deteriorating state of the rivers in his neighborhood, Patricio started an online petition asking the City to include in the constitution the cleansing and rescue of Mexico City's rivers.

Patricio's petition in Change.org gathered more than 17,000 signatures. Even though he was not old enough to cast a vote for the Constitutional Assembly that approved the constitution, his voice was part of the group of citizens whose proposals were included in the Constitutional draft. Now, Mexico City has to set forward a 20-year programmatic strategy towards the recovery of its rivers, water bodies and resources (article 16, Section B of Mexico City’s Constitution).

Patricio’s story is an example on how Constitución CDMX platform achieved its objective of including the voices of all those who wanted to participate in the drafting process of the constitution, regardless of their citizenship status, background, age or educational level. Moreover, his involvement and engagement in the process went beyond the traditional conception and mechanisms of electoral democracy, and even participatory democracy, that demand a minimum age to take into consideration the opinions and needs of many members of the community.

Institutional Impacts

Mexico City now has a constitution created through a popular co-creation process that managed to channel hundreds of thousands of citizen inputs and efficiently process them into useful insights. Besides the benefits this open process represents, it is important to note that the most progressive aspects in the constitution have their origin in the civic engagement process: Marriage equality, the explicit recognition of the Right to the City, rights of indigenous and aboriginal peoples, cultural rights, pro-choice policies, marijuana consumption, and other aspects of the constitution were supported by citizens’ petitions and proposals delivered through Constitución CDMX.

By combining a process of self-selected public engagement with a selection process, where members of the constitutional assembly were, at least in part elected, the City was able to enhance the legitimacy of the process.

Being a progressive hub in the middle of a highly conservative country, Mexico City managed to imprint in its new constitution the will of its people to continue to lead the Human Rights agenda, the recognition of liberties, and the protection of diversity, despite Federal opposition to these subjects. On an international scale, this document set a high bar for cities worldwide in the acknowledgement and recognition of new approaches to urban challenges for the 21st century.

Approximately 84% of the content produced by this co-creation scheme was approved by a qualified majority in the Constitutional Assembly and entered into force as Mexico City’s first constitution on September 17th, 2018. The required majority couldn’t have been reached by the Mayor’s political allies on their own, but was made possible by a citizen-led process for developing the new constitution.

The depth of public engagement in the process can be demonstrated in the explicit recognition of it made

by the

Mexican Supreme Court in its decision regarding

the constitutionality of the whole process, which was challenged by the Federal Government once the

constitution was

approved. The Justices argued that by having representatives of both persons with disabilities and indigenous

peoples

participating through the online petitions facilitated by the platform, Mexico City complied with the

international

consultation requirements that protect these vulnerable groups from any normative modification that could

potentially

affect them.

Risks and Challenges

Governments around the world are facing the challenge of rebuilding trust with citizens. The strategy implemented by Mexico City demonstrates that while opening up decision making processes will usually cost additional time and resources, investing in openness and co-creation will ultimately lead to more reliable results.

Mexico City’s constitutional process took place within a complex political and social context. The main challenge the team initially encountered when asking the citizens to participate through the platform was the lack of trust in the process. The partnership established with Change.org was a key element to regaining citizen trust. Even though the survey Imagina tu Ciudad was originally expected to be the participatory mechanism with a critical mass of users, the petition-making scheme turned out to be the most popular among users. The team behind the strategy attributes this to the fact that the mechanism was branded with the Change.org name and the platform already had a well-known reputation.

Another challenge for the implementation of Constitución CDMX was the digital divide that is still present in Mexico City. Even though the capital city ranks highest in the national measurements of households with internet access, this citywide initiative required the government to offer the opportunity to participate regardless of the people’s ability to access the digital platform. To address this challenge, the city deployed digital kiosks to reach citizens on the streets and public spaces.

Figure 3: High school volunteers and digital kiosks in Mexico City’s Plaza de la

República

Photo credits: Laboratorio para la Ciudad.

This outreach strategy was implemented in collaboration with the National Polytechnic Institute’s High School students. A gamification strategy was designed to encourage them to recruit people to take part with awards for those who attracted the most participants. The teams used social media as well as photos and videos to certify the participation of citizens in different public spaces and public transport stations. When technology failed and the digital kiosks were not able to access the platform, the students designed an analog version of the surveys and carried on with the civic engagement in flea markets, subway stations, and other places that did not have internet coverage.

Figure 4: High school volunteers surveying people in the streets.

Photo credits:

Laboratorio

para la Ciudad

Figure 5: High school volunteers surveying in Mexico City’s flea markets.

Photo

credits:

Laboratorio para la Ciudad

Outcomes

Constitución CDMX was able to garner international media’s attention, mainly due to the unprecedented collaboration with Change.org and the fact that the strategy was aiming to amass inputs from a diverse 20 million inhabitant metropolitan area. Specialized media outlets also highlighted how this CrowdLaw project was able to integrate opinions, ideas and proposals of the people that the constitution would eventually serve, going beyond the traditional conception of constitutional affairs being dealt with by a small elite, well-versed in constitutional law..

Moreover, the final document is considered to be the most progressive constitution in Latin America, and it has been recognized by the United Nations as a “historical document that addresses the central challenges of development and peace” and as “a guide to fulfill the universal, indivisible and progressive nature of human rights, the Sustainable Development Goals, and the 2030 Agenda.”

Numbers and Results

- 64.41% of participants were between 18 and 34 years old.

- 69.9% of visits to the platform were made from a mobile device, 25.31% from a desktop, and 4.7% from tablets.

- 15% of all visitors returned to the platform a second time.

- The Metropolitan Area of the Valley of Mexico concentrated 63% of all visits.

- The State of Jalisco 4.75%, Nuevo León 3.5% and Baja California 3.01%

Petition-making mechanism:

- 341 proposals, more than 400,000 unique followers

- Reception of proposals went on from March 30 to July 15, 2016

- Petitions that exceeded 10,000 signatures but fell short of 50,000: 9

- Petitions that exceeded 50,000 signatures: 4

- Petitions between 1,000 and 5,000 signatures: 7

- Petitions between 100 and 900 signatures: 44

- Petitions with less than 100 signatures: 282

- Number of unique supporters: 274,644

- Total number of supporters: 427,815

- 35.8% of the supporters signed more than one petition

- Number of Change.org users following Constitución CDMX updates: 479,212

Imagina tu Ciudad survey.

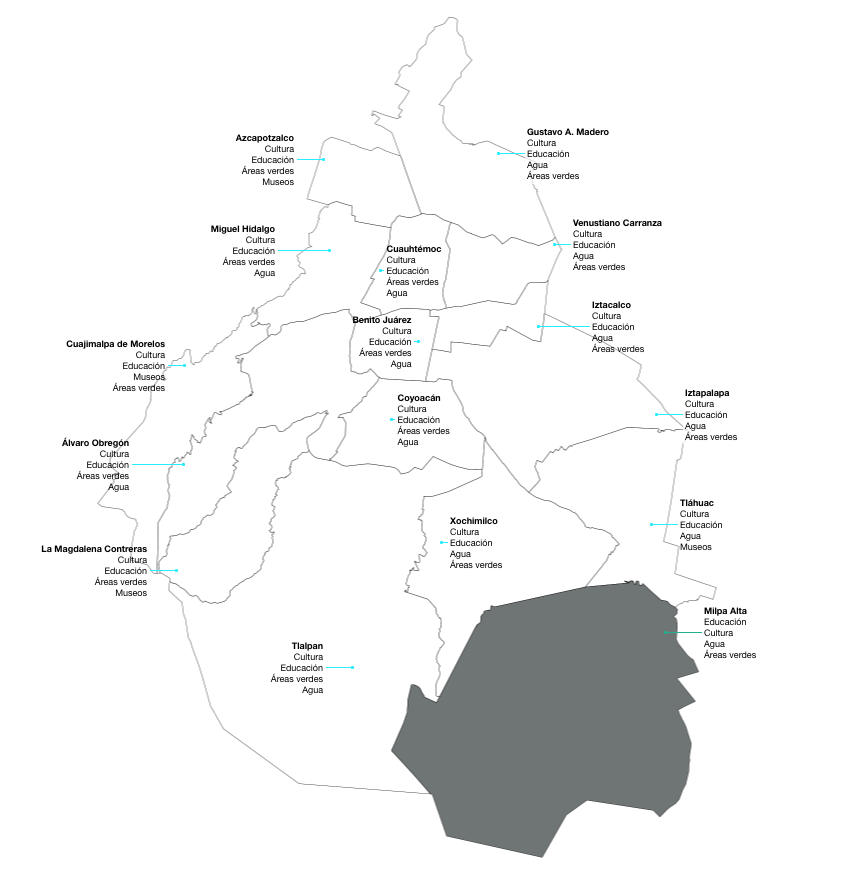

The influence area of this component of the strategy was all of Mexico City’s 16 boroughs. The 30,000 georeferrentiated answers had representation of 1,474 neighborhoods, accounting for 90% of all the neighborhoods in the city. Also, the Imagina tu Ciudad survey database is available as open data, providing Mexico City’s inhabitants with a raw resource for prospective analysis of their communities, and citizens from all over the world with input to further explore conversations around urban futures. This database has been used by Laboratorio para la Ciudad during the fifth edition of its Open Government Encounter, where it was the main input for a data visualization workshop, and it served as well for the definition of the challenges for the second edition of the Code for the City experiment.

- Number of effective surveys in the Metropolitan Area: 30,143

- In Mexico City: 26,040

- In the conurbated municipalities: 4,094

- Number of surveys conducted by high school volunteers: 14,934

- Number of volunteers: 183

- Total amount of hours of volunteering: 1,494 hours

Citizen-led events registration mechanism.

- Registered citizen events: 55

- Essays with conclusions uploaded to the collaborative editing platform: 26

- Number of comments in all essays: 17

- Events with most visits on the platform:

- Forum of Proposals for the Constitution of the CDMX, organized by the National Bar of Lawyers, on April 5, 2016. 509 visits.

- The Constituent Marathon, organized by private and public universities present in Mexico City on April 15, 2016. 496 visits.

- Forum on the Right to the City in the Constitution, on May 30, 2016. 323 visits.

PubPub: collaborative editing platform

- 100 essays uploaded on the platform.

- 1000 comments received in the published documents.

Users’ experience and perceptions after engaging with Constitución CDMX

Thanks to the interaction between the group of petition-makers and the city officials, perceptions of, and confidence in, one another changed. Francisco Fontano, the first petition-maker to reach the benchmark of 10,000 signatures, is a sports journalist that advocated for the constitution to include a minimum requirement of green areas per capita. Manuel Granados served as Mexico City’s General Counsel, in charge of coordinating the works of the Drafting Group as well as the interactions with citizens derived from the platform. Before Francisco got to present his proposal to the General Counsel and 3 representatives of the WG, he told the Lab’s team about how nervous he was meeting firsthand a senior government official. What Francisco didn’t know is that Granados was even more nervous to hold a working session with an unknown citizen representing more than 10,000 other people. Before this collaboration scheme took place, Change.org was regarded by public officials as a tool for opposition members, activists or pressure groups to generate bad press for Government, and thus its real usefulness was regarded with skepticism.

As these meetings continued, trust between both parties evolved. This renewed relationship based on trust can be perceived in the series of interviews Laboratorio para la Ciudad conducted with the petition-makers, as well as in the messages they sent to their thousands of supporters in their petitions.

Mexico City’s approach of offering a series of diverse approaches and mechanisms, each of which was accompanied by a firm commitment from the City to act on the engagement, offered a more democratic, citizen-friendly and replicable method that can be replicated for any legislative crowdsourcing strategy.

Map 1: Imagina tu Ciudad by borough.

“What is Mexico City’s most valuable asset?”

Credits: Urban Geography Department, Laboratorio para la Ciudad.

Map 2: Imagina tu Ciudad survey participation by neighborhood.

Credits: Urban Geography Department, Laboratorio para la Ciudad.

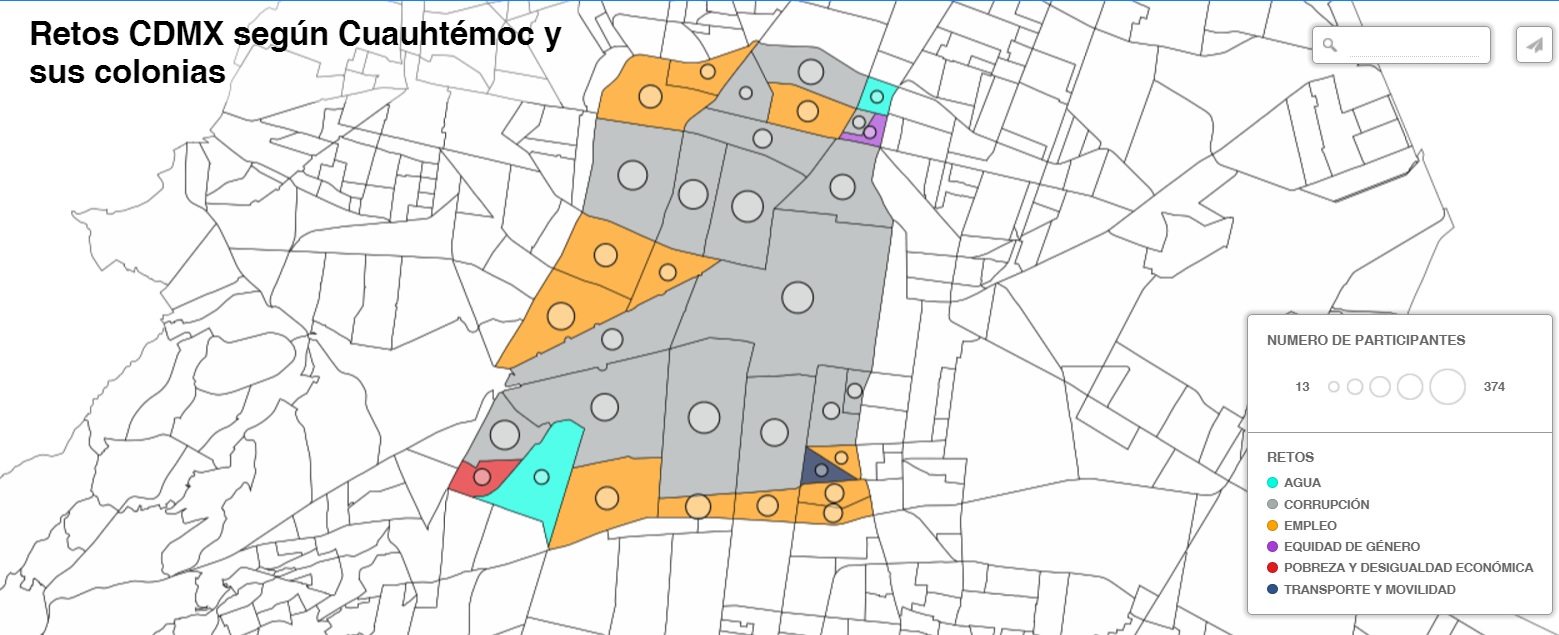

Map 3: Cuauhtémoc borough and its neighborhoods.

“What are Mexico City’s three main challenges for the next 20 years?”

Credits: Urban Geography Department, Laboratorio para la Ciudad.

Table 1: Online petitions that surpassed the established thresholds of digital signatures in the Constitución CDMX strategy.

|

Online Petition |

Petition-maker |

# of signatures |

Constitutional Draft |

Final text of the Constitution |

|

Publicity of tax records, declarations of interest and properties owned by public servants. |

Alejandro Ortega Salinas |

63,508 |

Art. 70, 2 |

Art. 64, 2. |

|

Right to a good Public Administration (anti-corruption) |

Alejandra Núñez |

50,386 |

Art. 12, A |

Art. 2, 3. Art. 7, A; Título Sexto |

|

I want Mexico City to be a Smart City – #SmartCDMX |

Nicolás Ávila Pineda |

50,664 |

Art. 21, F, b |

Artículo 7, 8-C |

|

Guardianship and protection for animals in the Constitution CDMX |

Nydia Cervera |

54,157 |

Art. 14, I |

Art. 13, B |

|

Guaranteeing minimum areas of green spaces per inhabitant |

Francisco Fontano Patán |

39,182 |

Art. 17, A |

Art. 16, 3. |

|

Sustainable mobility for |

Alejandro Posadas Zumaya |

29,382 |

Art. 17, E |

Art. 12, E. Art. 16, H. |

|

Digital Rights and free and universal internet access in Mexico City. |

José Alberto Escorcia Giordano |

21,270 |

Art. 13, B, 1 |

Art. 8, C. |

An inclusive Constitution for Mexico City (Measures for people with disabilities) |

Juventino Jiménez Martínez |

16,803 |

Art. 16, F |

Art. 11, G. |

|

¡Rescue Mexico City’s rivers! We need a comprehensive hydric policy in Mexico City |

Carlo Patricio Pérez Castillo |

17,306 |

Art. 14, H |

Art. 16, A, 3, 4, B. |

|

Mexico City’s Constitution with all the rights for all the women |

María Fátima Moneta Arce |

14,889 |

Art. 4 |

Art. 4, B, 4. |

|

CDMX: maternity and paternity leave for all |

Sonia Lopezcastro |

15,010 |

Art. 15, E, e |

X |

|

LGBTI rights in our new Constitution |

Alianza Ciudadana LGBTI Roberto Pérez Baeza |

11,322 |

Art. 16, G |

Art. 11, H. |

Footnotes

[1] Due to inactivity, some petitions have been disabled by Change.org. Thus, the Movement’s mini-site might not currently display peak numbers.