Mudamos

The Citizen Initiative App

Read Time

Brief View 8 MINS

Full Story 25 MINS

Briefing Notes

How Does It Work?

Mudamos is a mobile application that enables Brazil’s citizens to participate in lawmaking by proposing their own bills and signing onto one another’s proposals using verified electronic signatures.

Mudamos comprises three parts: 1) The app’s secure and verifiable digital signature technology; 2) the process for proposing, analyzing and improving proposed bills; and 3) in-person Virada Legislativa (legal draft-a-thon) events.

- Mudamos App - Any citizen with a smartphone (Android or iOS) can download the app and register with his or her electoral ID, name and address, information which Mudamos keeps secure and verifies with Brazil’s Electoral Court. The app issues what is known as a cryptographic key pair, a small piece of digital code used for verification. One half of the key is stored on the user’s phone and the other with Mudamos, which makes it possible to authenticate a person’s signature. In this way, members of the public can draft and sign petitions in a way that is verifiable and secure.

- Legal Analysis Team - To address the volume and quality of submissions, Mudamos’s creators have designed a volunteer lawyer program. Since January 2018, ITS Rio uses crowdsourcing to engage young lawyers to assist in the analysis of the proposals. The Mudamos volunteer legal team performs a legal analysis to verify whether the draft bill has all the constitutional requirements to be framed as a citizens' initiative bill. If it has all the constitutional requirements, the bill is uploaded on the platform and it is published for signature gathering immediately. If it has not, the bill’s author receives a feedback report based on the analysis recommending changes or explaining why the proposal cannot be accepted as a citizens' initiative bill.

- Virada Legislativa Events - To foster lawmaking literacy and help citizens to create their own draft bills, ITS organizes Virada Legislativa. The Virada Legislativa is a one-day in-person event to develop draft bills collectively -- a draft-a-thon -- addressing a single issue and within a timeframe.

What are the outcomes?

With the massive adoption within a few months after its launch, Mudamos has not only been leading a technological turn in politics, but also fostering institutional and cultural changes by making the once-theoretical possibility of direct democracy real in practice. Since Mudamos has been released, the platform has received more than 8,000 draft bill proposals. In its first month, Mudamos was downloaded by more than 250,000 people and by October 2018, more than 700,000 people had downloaded the app. Over half of those are active users. Since Mudamos’s launch in March 2017, several legislative bodies have enacted new measures to recognize the use of Mudamos as an official channel for participatory lawmaking.

What does it cost?

Mudamos is a free application that can be downloaded from mobile application stores.

What are the benefits?

- Mudamos is a secure and affordable way for people to express themselves politically by drafting bills for legislative consideration or signing onto bills.

- The technology ensures that signatures are trackable and verifiable.

- Mudamos reduces the reliance on paper-based systems for signature collection, which in turn reduces costs.

What are the risks?

- Mudamos’s electronic signature is not a national standard and the major risk to the Mudamos project is the contesting of the validity of its signatures by legislative bodies. Since an electronic signature standard is not established by law or even by a House of Representatives rule, the decision whether or not to accept Mudamos signatures is made subjectively.

- Another risk faced by Mudamos is the low adoption rate of the app (350,000 active users) in relation to the number of signatures required to propose a national level draft bill (1.5 million)

Introduction

Brazil became known for its participatory democratic institutions and pioneering participatory budgeting in the city of Porto Alegre in 1986, a deliberative process that enables ordinary citizens to determine how a portion of the municipal budget will be spent. Now PB is in practice in more than 1,500 cities around the world. Once again, Brazil is leading the world with a new, secure and verifiable way for citizens to write draft bills and vote to support that citizen proposals be considered by the legislature. With 700,000 people signing up in the first year of this CrowdLaw initiative, Mudamos (We Change) could be the linchpin to enabling collaborative drafting of legislation and unlocking the power of direct democracy in practice.

Mudamos is a mobile application that enables Brazil’s citizens to participate in lawmaking by proposing their own bills and signing onto one another’s proposals using verified electronic signatures. Any citizen with a smartphone (Android or iOS) can download the app and register with their electoral ID, name and address, information which Mudamos keeps secure and verifies with Brazil’s Electoral Court. The app issues what is known as a cryptographic key pair, a small piece of code used for verification. One half of the key is stored on the user’s phone and the other with Mudamos, which makes it possible to authenticate a person’s signature. In this way, members of the public can draft and sign petitions in a way that is verifiable and secure.

Brazil’s Constitution provides several direct democratic mechanisms, including the referendum, plebiscite, and citizens' initiatives. The initiative mechanism allows any citizen to propose a draft bill to the lower house of municipal, state or federal legislatures. If the proposal gets the requisite number of signatures from registered voters in support then the campaign organizators present the bill before the House. Once the signatures are verified, the Speaker assigns a House committee to start bill discussion that could lead (or not) to the bill becoming a law. At the federal level, the minimum amount of signatures is 1.5 million, which is problematic to organize using paper-based petitions. Popular initiatives to collect signatures are often paper-based which, apart from being costly, also present problems of transparency and integrity. In fact, no citizen bill has ever been approved at the national level due to the verification barrier and participation costs.

The Institute for Technology and Society (ITS Rio) created Mudamos in 2017 to reduce the high costs of creating paper-based petitions by offering a verifiable online mechanism for the creation and signing of citizen petitions offering a robust means of participation that, in turn, should help to raise citizens’ degree of trust in political institutions and contribute to the construction of participatory rules and norms. Since its launch, the Mudamos CrowdLaw initiative has had significant impact:

- The large numbers of downloads, petitions and signatures enabled by the tool has positively impacted political culture.

- The availability of a secure and verifiable petition mechanism has made a constitutional provision on direct democracy real in practice.

- It had led to the creation of a model legal framework regarding electronic participation and its adoption at different institutional levels

In this report, we will describe the background conditions that allowed Mudamos to take off, the design and key features of the process and the tool. Following this section, we will describe the institutional impacts of the project in more detail and, finally, share some lessons learned from the experience.

Background

Since the Federal Constitution was approved in 1998, Brazil has had a law which allows citizens to propose draft bills once the petition has met the requisite threshold for signatures. At the federal level, a draft bill needs a minimum of 1.5 million verified signatures to be presented to the Lower House. The logistical barriers to collect and validate these signatures, together with voters’ identifications and addresses, are the greatest obstacles in this process.[1] As a result, to date no citizen drafted bill has ever been approved. In a few instances, interested politicians have “adopted” the draft bill and presented it as if they authored it, eliminating the need for verifying the signatures. In other words, members of Congress act as proxies for citizens to claim their direct participation rights. At the national level, the following draft bills were proposed by citizens and "adopted" by a congressman:

|

Law |

Signatures |

Formal proponent |

Congress discussion |

Law subject |

|

8.930 from 1994 “Daniella Perez Law” |

1.3 million |

Executive branch |

From 1993 to 1994 |

Increase penalty for homicide crimes. |

|

9.840 from 1999 Electoral corruption law |

1.6 million |

Congressman Albérico Cordeiro |

1999 |

Against bribes for voters and other electoral offenses. |

|

11.124 from 2005 National Housing Fund |

1 million |

Congressman Nilmário Miranda |

From 1992 to 2005 |

National Housing Fund creation. |

|

135 from 2010 "Cleanstate Law" |

1.6 million |

Congressmen Antonio Carlos Biscaia, Arnaldo Jardim, Camilo Cola, Carlos Sampaio, Celso Maldaner, Chico Alencar, Domingos Dutra, Dr. Rosinha and others.[2] |

From 1993 to 2010 |

It makes ineligible for eight years any oficial who has the mandate revoked, resign to avoid prosecution or is condemned by decision of a court majority opinion. |

|

Bill 4.850 from 2016 Ten anti-corruption measures |

2 million |

Congressmen Antonio Carlos Mendes Thame, Diego Garcia, Fernando Francischini, João Campos and others.[3] |

Since 2016 |

Create new measures to fight against corruption and increase penalties for who is convicted by corruption crimes. |

Table 1: National citizens' initiative draft bills in Brazil. Source: The author.

One of the most controversial citizen-drafted bills was called "ten anti-corruption measures." In March 2015, the Ministério Público Federal (“MPF”), the Brazilian Federal Prosecution Service, released 10 proposals to reinforce the fight against corruption in the country, and in July 2015, started a campaign to gather signatures in various Brazilian cities. Less than five months later, in December 2015, the campaign reached 1 million signatures and two months later it overcame the 1.5 million signature threshold. On March 29, 2016, members of the Federal Prosecution Service and civil society actors presented more than 2 million signatures to the National Congress in support of the draft bill.

In much the same way that prior citizen-drafted bills were presented to Brazil’s Congress in the past, a group of members of Congress formally "adopted" the initiative (See Table 1), introducing it as formal legislation. On the next day, a fast track discussion for the Bill was approved by the legislature. While the discussion in the House of representatives received a lot of public attention, the controversial side of the new proposal was revealed when some members of Congress stated the new Bill would give too much power to the Federal Prosecutors. Many of the more stringent measures were greatly modified or removed entirely by the congressmen. Federal Prosecutors accused members of Congress of trying to stop the "fight on corruption" while House representatives claimed the challenged provisions were authoritarian and unconstitutional. In the end, only two of ten measures were approved.[4]

On November 30th, 2016, the diluted Bill was ratified by the House and sent to the Senate. However, before it was discussed in the Senate, Justice Luiz Fux of the Supreme Court decided the Bill should be sent back to the House due to the "deviant practices,” employed during its consideration by the House.[5] Justice Fux also decreed that it was necessary to check all the citizen signatures provided in support of the Bill. The verification process started in February, 2017 and finished a month later. It was the first time the signatures on a popular petition had been vetted. But according to a House staff report, this process involved little more than counting the signatures and ensuring complete information (e.g., name, electoral ID and signature), none of which was actually validated.[6]

Even though there is no publicly available information, off-the-record talks with some public servants in the House revealed that the signatures were not verified since the House did not have the means to proof two million signatures. Identification information in Brazil is held by the states' executive branches. At the national level, the Superior Electoral Court manages the country’s biometric signature program. It alone has the capacity to verify the signatures of all voting age citizens. The legislature does not have the means, by itself, to compare signatures with official citizen records. In addition, verifying signatures one by one could take a long time as the House does not have personnel adequate to the task.

Aware of this problem and proposing a way to use technology to overcome this challenge, the Institute for Technology and Society (ITS Rio) wrote a project proposal to create a mobile application to allow citizens to present electronic signatures in support of citizens' initiative draft bills. The app was developed by ITS Rio with funds from the Google Impact Challenge 2016 award. ITS Rio is a Brazilian NGO which designed Mudamos and conducted the project with the support of other companies and organizations. The development started in October 2016 and in April 2017, the app was launched simultaneously on Google’s Android Play Store[7] and Apple’s App Store.[8] In the first month, Mudamos was downloaded by more than 250,000 people and became the trending app on Brazil’s application stores, prompted by a viral video made by a Mudamos user and spread through the messaging platform WhatsApp with the message that now "people can participate directly in politics without any intermediary.""[9] One year after its launch Mudamos had been downloaded by more than 650,000 people. By October 2018 that number climbed to more than 700,000 people. Three factors made Mudamos possible at that point in time:

- Legal Framework: With an existing legal framework in place, citizen initiatives were theoretically possible but practically impossible due to the prohibitive cost and complexity. Digital tools bring down the cost of authoring proposals, obtaining and verifying signatures, thus creating greater incentives to political participation. It got stronger when political institutions perceived the necessity to update their norms to respond to this new digital scenario due to the difficulty of verifying signatures.

- Technological Viability: With the ever-growing interest and research into cryptography technologies, more professionals are discovering new applications for them. Mudamos created a cheap way to allow citizens to create strong signatures which are trackable and verifiable.

- Funding: The Google Impact Challenge award provided the necessary enabling capital to kickstart the project. The funding received was invested in hiring a team of specialists to design and program the app and support the project operations team.

Mechanics of Mudamos

Mudamos comprises three parts: 1) The app’s secure and verifiable digital signature technology; 2) the process for proposing, analyzing and improving proposed bills; and 3) in-person Virada Legislativa (legal draft-a-thon) events. Together, this combination of technology and process make this digital citizens’ initiative program workable in practice.

Mudamos online platform

Political behavior of both citizens and politicians has been changing rapidly together with new technological, social and political contexts: political participation is not exclusively in the offline world anymore, with institutions becoming receptive to digital engagement and the Internet.[10] Currently, thanks to the Internet and other technologies, it is possible to collect signatures throughout Brazil and verify them automatically. Digital signatures already had their relevance recognized and used in common civic procedures, as instituted by the Presidency Act MPV 2200/2001, and in legal acts, as instituted by Law 11419/06.[11] However, since the cost of obtaining official digital certificates is prohibitive, they did not gain widespread adoption and a mere .005% of Brazilians have them.[12]

Digital signatures based on certificates issued by the Brazilian government have the advantage that they are legally binding, meaning any documents signed using those certificates are recognized by any authority as authentic for any purpose, from the recognition of a debt to real estate transactions. However, when we talk about political rights, we do not need signatures to be that strong because people's support of causes are the expression of their political desire, not legal intent. Signature campaigns need only ensure that signatories have the constitutional right to sign the draft bill and signatures only need to allow for public scrutiny to audit the political support given to the bill.

Taking this into account, Mudamos created a way to allow people to sign draft bills using self-issued certificates using their own smartphones. The technology stack used by Mudamos is the same used by certificate authorities to issue certificates, excluding the fact Mudamos is not a recognized authority to issue legally-binding certificates. That is to say, while Mudamos-issued certificates cannot be used to authenticate a contract in court, nonetheless the signatures are technically unbreakable and verifiable and well-suited to the purpose of ascertaining citizen wishes but without the cost of doing through one of a handful of monopoly legal certificate providers. In short, Mudamos created a secure and affordable way for people to express themselves politically through digital means.

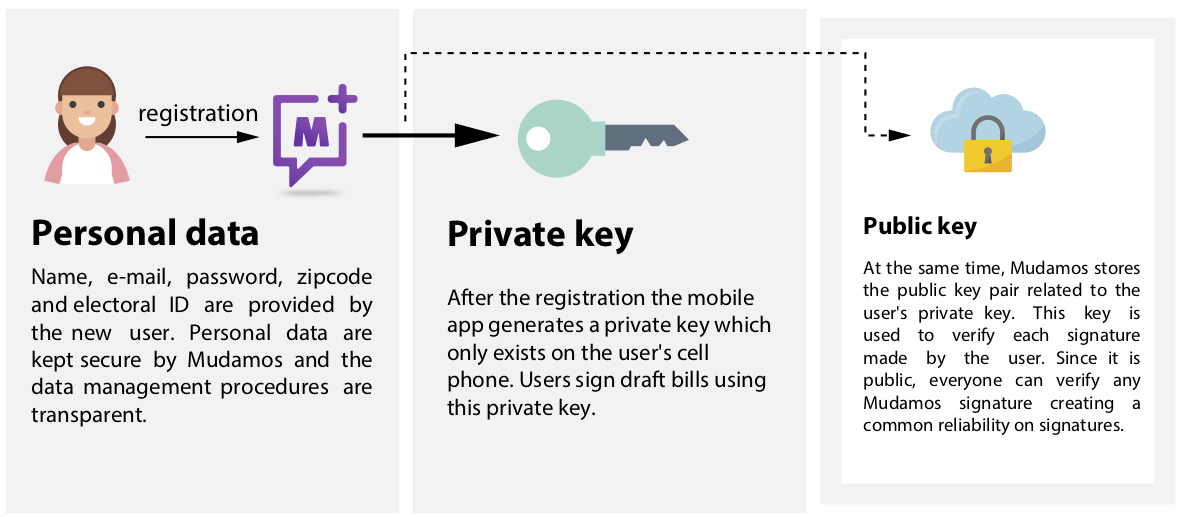

Anyone who has an electoral ID and a smartphone (Android or iOS) can download the Mudamos app and create or sign citizens draft bills listed on the platform. When Mudamos users install the app, they get a cryptographic key pair to secure their signature. The model established by ITS Rio for Mudamos assumes that no actor in the process of collecting signatures would have all the pieces of information necessary to produce new signatures. At the same time, all users would have access to the information they need to check any new signature generated within the system using asymmetric cryptographic techniques. This type of technique is based on algorithms that require a pair of keys, the first being private (that should remain secret) and the second being public; although they are different, the key pair is mathematically linked. The private key is used to create a digital signature while the public key is used to verify a digital signature (Figure 2).[13]The uniqueness of the signatures is guaranteed by the association of unique electoral ID number combined with the signature timestamp and the user’s private key. The private key generates a unique hash based on the data reported for signature. Verifiability is guaranteed by publishing the user’s public key along with the data given for signature and the signature hash. In order to make the whole process auditable, Mudamos publishes the signatures list periodically by registering the files in public blockchain networks.

The uniqueness of the signatures is guaranteed by the association of unique electoral ID number combined with the signature timestamp and the user’s private key. The private key generates a unique hash based on the data reported for signature. Verifiability is guaranteed by publishing the user’s public key along with the data given for signature and the signature hash. In order to make the whole process auditable, Mudamos publishes the signatures list periodically by registering the files in public blockchain networks.

Figure 1: Mudamos registration and key pair generation.

Figure 1: Mudamos registration and key pair generation.

Mudamos signatures are founded in three fundamental principles: uniqueness,verifiability and auditability.

The uniqueness of the signatures is guaranteed by the association of the unique electoral ID number combined with the signature timestamp and the user’s private key. The private key generates a unique hash based on the data reported for signature (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Mudamos sign process.

Figure 2: Mudamos sign process.

Verifiability is guaranteed by publishing the user’s public key along with the data given for signature and the signature hash. In this way, anyone interested in checking any signature has the capability to do so.

In order to make the whole process auditable, Mudamos publishes the signatures list periodically by registering the files in public blockchain networks (Figure 4), where they can be publicly scrutinized. This ensures that signature lists are immutable, and if an interested agent wants to audit the entire signing process, from the first signature collected, they have the capability to do it without relying on Mudamos or any other agent.

Figure 3: Regular signatures list publishing.

Figure 3: Regular signatures list publishing.

Proposing a Bill

Mudamos not only allows users to sign in support of a bill but also to suggest new draft bills for signature collection. To propose a draft bill, the user needs to answer the following questions: 1) draft bill name; 2) draft bill content; 3) which level the bill addresses (national, state, municipality); 4) video description (optional); 5) whether there is a law related to this draft bill (yes or no).

Figure 4: Welcome screen for draft bill proposing. Source: Mudamos Website.

Figure 4: Welcome screen for draft bill proposing. Source: Mudamos Website.

Legal Analysis

Since Mudamos has been released, the platform has received more than 8,000 draft bill proposals. In its early days, the Mudamos legal team consisted of a single specialist who was responsible for analyzing the large number of proposals. To address the volume, Mudamos’s creators have designed a volunteer program. Since January 2018, ITS Rio uses crowdsourcing to engage young lawyers to assist in the analysis of the proposals.

The volunteer program had 63 applications, mostly by young lawyers. Many were from Rio de Janeiro, but all regions were represented in the applicant pool. After an evaluation process, Mudamos selected 26 volunteers who attended a course supported by ITS. The course was delivered as a webinar (online) in March 2018 and covered topics such as the legislative process, draft bill proposers, communication protocol and sharing experiences.

Before draft bills are published in the platform, the Mudamos volunteer legal team performs a legal analysis to verify whether the draft bill has all the constitutional requirements to be framed as a formal petition. If it satisfies the constitutional requirements, the bill is uploaded on the platform and published for signature-gathering immediately. If it does not, the bill’s author receives a feedback report based on the analysis recommending changes or explaining why the proposal cannot be accepted as a citizens' initiative bill.

Virada Legislativa Events

Eighteen months after its initial release, Mudamos improved not only its software platform but also its workflow. As new features were added it was necessary to create procedures to face new project challenges. When Mudamos began to accept new draft bill proposals, it quickly became clear that people did not know how to format their petitions as a formal bill.

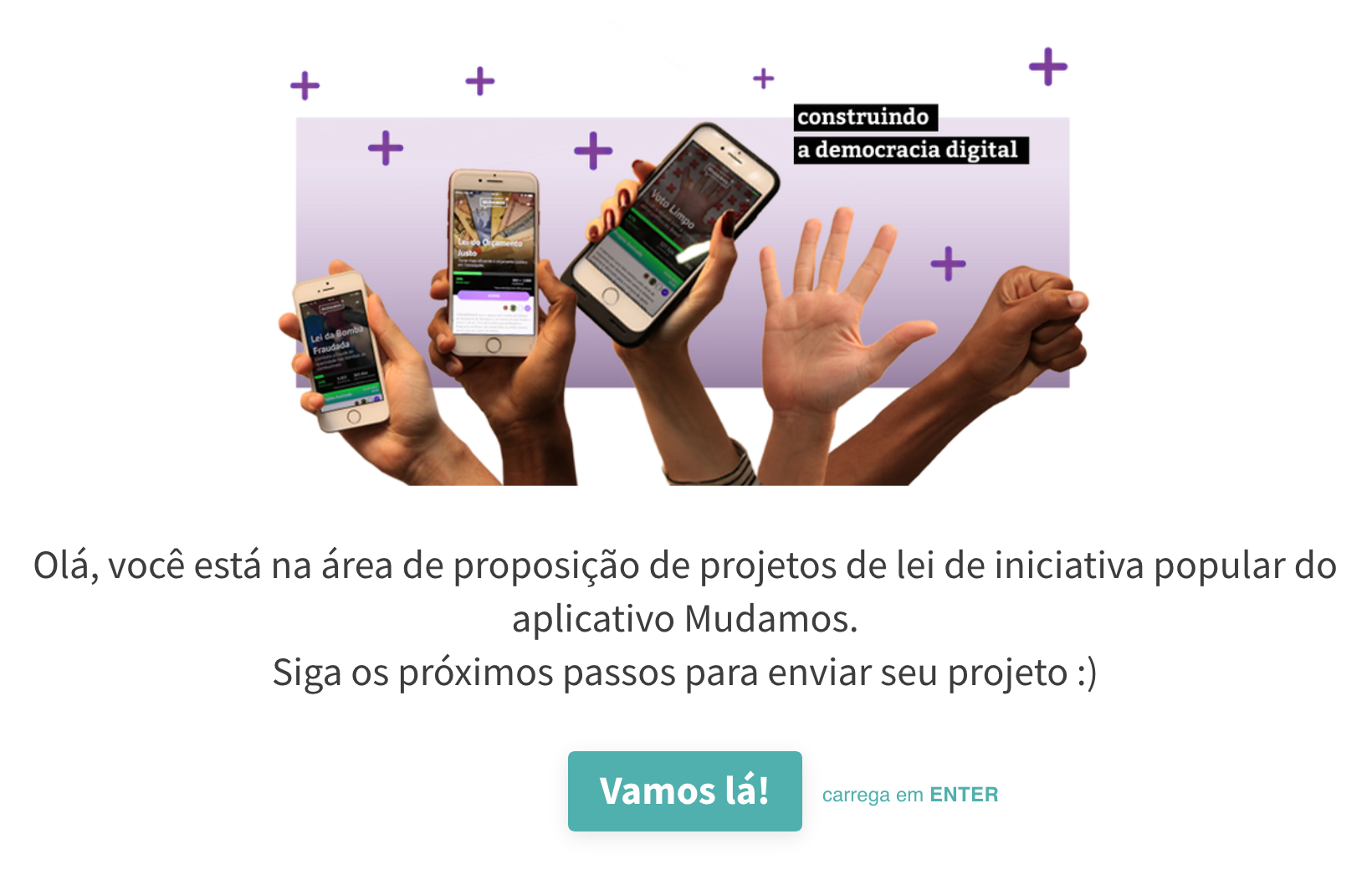

There were many good ideas that were not properly formatted as a draft bill proposal, putting more strain on the volunteer legal team get the bill into shape. To overcome this situation the Mudamos team created a side project called Virada Legislativa (legal draft-a-thon). The Virada Legislative is a one-day in-person event to develop draft bills collectively -- a draft-a-thon -- addressing a single issue and within a timeframe.

The event is divided into stages. To focus on establishing the basis for the debate and an introductory reflection moment for participants to recognize each other and their ideas in the group, the first stage consists of a multi-stakeholder panel and the next stage is a fishbowl conversation with the audience, including the first stage panelists.[15]

The following three steps are directed at the actual drafting of the proposals and based on the first reflections: address the draft bill main objective, write down general definitions and, finally, draft bill devices. At this point the group is divided into thematic areas taken as the result of the two first stages of the draft-a-thons. All working groups are supported by mentors (both specialists in the issue addressed as well as legal experts) to draft the bills.

The last two stages are the “test” of the bill and its publication on Mudamos. For the “test,” the group chooses a representative to present the proposal to a standing committee formed by parliamentarians who play the role of consultants to improve the bill. The final version of the draft bill is published on Mudamos and then the signature collection starts.

Figure 5: Draft-a-thon phases and methodology

Figure 5: Draft-a-thon phases and methodology

“Virada Legislativa” is ruled by four principles:

- multi-stakeholderism: the more diverse the sectors participating in the activity, the stronger will be the proposal drafted, as it will take into account various points of view and interests.

- collaboration: all the participants co-create the proposals, exchanging ideas and trying to reach consensus, with active listening and respectful communication. This is mediated by group facilitators previously trained by Mudamos’s team.

- open call and online/offline interaction: the activity is open to the participation of all citizens, without any kind of selection. Despite the draft-a-thon taking place in person, it is connected to the online space through tools such as live streaming, commenting and suggesting on digital platforms.

Figure 6: Picture from the first Virada Legislativa held in the city of João Pessoa, state of Paraíba.

Photographer: Yasmin Tainá.

Figure 6: Picture from the first Virada Legislativa held in the city of João Pessoa, state of Paraíba.

Photographer: Yasmin Tainá.

The first "Virada Legislativa" took place in João Pessoa and addressed urban mobility, having the collaboration of civil society organizations, academia, and local public administration. More than 100 people participated in the activity as well as 20 group facilitators and 15 city councillors. The participants collectively drafted five proposals on issues such as transport integration, sidewalk standardization and open data on the transport system. Another “Virada Legislativa” took place in Rio de Janeiro on entrepreneurship. In this legal draft-a-thon, one draft bill was developed on decreasing the highly bureaucratic procedures for opening a company in the country. Besides these “Viradas,” various workshops on this methodology have been conducted, aiming at multiplying its applicability.

Figure 7: fishbowl conversation with a counselor talking at the same level of other participants. Photographer:

Yasmin Tainá.

Figure 7: fishbowl conversation with a counselor talking at the same level of other participants. Photographer:

Yasmin Tainá.

To date, there have been three Virada Legislativa events with 200 participants leading to new 12 draft bills on the platform which altogether have received 6,014 signatures. Despite the low levels of subsequent participation on the app, the live events had a significant impact. The best of the Viradas Legislativas saw city councillors and citizens sitting down together to collaborate around law making. The city of João Pessoa, where two Viradas Legislativas took place, changed their participatory culture from an ordinary consultation process to a real collaboration between citizens and officials.

A Note on Lower Levels of Government

As noted, the Constitution provides for citizen petitions at every level of government. With the advent of the Internet, every branch of government has begun to digitize in some way. For example, the executive branch launched a Digital Transformation Agenda.[16] Although the judiciary has digitized the paperwork involved in legal proceedings, many states and cities in Brazil still face challenges with digitization.

Regional legislative houses and local councils generally do not have the technological resources to update their procedures for accepting citizen claims. Among all the Brazilian states and capitals, only Rio de Janeiro,[17] Santa Catarina[18] and Porto Alegre[19] have institutionalized citizens' initiative electronically through the Internet. The state of Amapá[20] announced the launch of a digital portal to receive such draft bills, however it is still not available. In the state of São Paulo, Law 162 of 2008 was presented to "regulate popular initiative started in the World Wide Web." However, the bill has still not been voted on, even after a positive legal advice by the Commission of Constitution and Justice of the Legislative Assembly of the State of São Paulo. In Curitiba, bill 005.00189 from 2013 also allows the collection of signatures on such draft bills digitally, but it is still in the process of being implemented. Against this backdrop of underdevelopment in the states, Mudamos may be the best available model for effective direct democratic participation and support for representatives and public servants in their aims to modernize.

Participation

Participation across the different aspects of the program is demographically diverse, sometimes in surprising ways. Although the ITS Rio team strove to reach young people with the project, however, the platform has become more popular among older people in Brazil. Mudamos platform users have a high average age of 43.7 and this average is increasing as time passes. At the outset the average age was 41. It is too early to draw a conclusion, although the appeal for older voters may be the result of generational views about political engagement and trust in government. While older generations may be attracted by the time and cost saving of online participation, younger people take the online aspect for granted but want to be sure that their participation matters and will be impactful.

Of the 700,000 signed up, half are active users. Brazilian cities with the greatest number of users are São Paulo (28,651), Rio de Janeiro (24,795), Brasília (22,748) and Belo Horizonte (8,589). This distribution on Mudamos for the first three cities almost represents what was counted by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics on the last census.[21] Mudamos is well represented geographically throughput the country, but the gender distribution is heavily skewed as the vast majority of platform registered users are male (74%).

The platform and volunteers differ greatly in average age. In its volunteer program, Mudamos currently has 26 young lawyers working on draft bills proposal analysis and review. They are spread over different regions as follows: sixteen in the Southeast; two in the South; two in the Midwest; two in the Northeast; one in the North; and two overseas. Mudamos volunteers are coordinated by Mudamos staff at ITS Rio, who are responsible for distributing proposals among volunteers. Seventeen of the volunteers are women and the overall average age is 25 years.

Finally, three editions of the Virada Legislativa have had more than 170 participants. If we add in all the participating experts and stakeholders from different sectors, the number would be over two hundred. The gender distribution among all legislative draft-a-thons participants was balanced between men and women. The average age of all participants across the three editions of Virada Legislativa is 35 years - in between the app’s users and the volunteers who manage the program.

Institutional and Cultural Changes

With the massive adoption within a few months after its launch, Mudamos has been leading, not only a technological turn in politics, but also fostering institutional and cultural changes by making the once-theoretical possibility of direct democracy real in practice. Perhaps the most significant impact of the program is the transformation of political life from a largely closed door to a more participatory process. Before Mudamos, Brazilian citizens were generally not aware they could propose draft bills. After Mudamos was released they have been excited with the "new" institutional mechanism available to them to influence politics. At the same time, politicians have started to pay attention to Mudamos and its ability to ease the signature gathering for citizens' initiatives draft bills.

At the national level, in late 2016 and throughout 2017, Congress was discussing the issue of political reform. In April 2017, a few days after Mudamos’s first release, ITS Rio was invited to discuss and present Mudamos to the congressional Political Reform Committee, led by its speaker Congressmember Vicente Cândido. That hearing led to draft bill 7574 of 2017, which would update the citizens' initiative law to recognize the new electronic mechanism.[22] The bill is still under negotiation in the National Lower House and is ready for a floor vote. In addition to this legislative reform, Mudamos supported the efforts of members of Congress to facilitate the use of electronic signatures for civic participation by addressing congressional internal rules and procedures. In 2017, Congressman Alessandro Molon presented two proposals to make Congress ready to receive electronic signatures for citizens' initiative draft bills.[23]

Taking into account the difficulty to make change at the national level, the Mudamos team also directed efforts on local changes. In João Pessoa, capital of Paraíba state, municipal law 13041 (2015) regulates the use of electronic signatures in petitions.[24] However, since its approval, there have been no adequate technical tools to give effect to this law. Recognizing Mudamos as a cheap and accessible technical option, on May 9, 2017, at a public ceremony held by the city council, Mudamos was designated the official channel to present citizens' initiative draft bills.

In addition to Mudamos being widely recognized by the general public, some public servants and representatives have also looked to make it the main channel for proposing draft bills in other states. With their experience in João Pessoa serving as inspiration for institutional change, the Mudamos team created a draft legal framework to support both legislative houses of Congress with updating their procedures. This legal framework is a collection of documents that can be used by representatives and public servants as a template to create new norms to allow electronic signatures to be accepted in their legislative houses. It is equally useful for state and local legislatures as well as the federal level. Following this framework, the City of Divinópolis in Minas Gerais institutionalized Mudamos through a memorandum of understanding where ITS Rio supports the efforts of their legislative houses to update their norms and procedures to be prepared to accept electronic signatures.

In addition to changing norms and practices, Mudamos has also strengthened Brazilian political culture and literacy on collaborative law building. Since the launch of Mudamos, the people have demonstrated they have a strong will to participate and good ideas to propose. Mudamos has received more than 8,000 ideas for possible draft bills, but none of the proposals were, in fact, written as such. Without any experience with political participation, the knowledge of how to participate in political processes is under-developed. The lack of experience combined with the arcane and legalistic nature of the lawmaking process, which is very jargon-filled and detached from citizens’ everyday reality, have given rise to anticipated challenges of needing to “translate” between the needs and desires of ordinary citizens and the formalistic demands of the legislative process.

Figure 8: Final picture of João Pessoa's Virada Legislativa.

Figure 8: Final picture of João Pessoa's Virada Legislativa.

ITS Rio addressed this problem by developing the “Virada Legislativa.” But the need for new mechanisms to strengthen people’s ability to participate in CrowdLaw processes -- and the ability of institutions to make use of their expertise and input -- is a still ongoing process.

Risks and Challenges

Despite all it has to offer, Mudamos’s electronic signature is not a national standard and the major risk to the Mudamos project is the contesting of the validity of its signatures by legislative bodies or in courts. Actually, Mudamos is facing a challenge from the legislative house of the Federal District, where Mudamos signatures were not accepted in support of a citizen’s initiative draft bill, which called for reducing the House budget. Since an electronic signature standard is not established by law or even by a House of Representatives rule, the decision whether or not to accept Mudamos signatures is discretionary. To mitigate this scenario, ITS Rio drafted a report about citizen initiatives bills arguing that electronic signatures should be accepted based on the current legislation.[25] In addition, the Mudamos team has been talking to members of Congress and other leaders, pushing for legislation to standardize electronic signatures. The Mudamos legal framework is another approach to build dialogue bridges between technicians, activists, and legislative houses to support local and national legislative change.

Another risk faced by Mudamos is the adoption rate of the app (350,000 active users) in relation to the number of signatures required to propose a national level draft bill (1.5 million). Despite the fact that Mudamos had at least four viral waves since its launch, new user registrations are not growing at a substantial rate. Continuous engagement on Mudamos requires fostering internal variables, such as better user experience and strategic communication for action, and external variables, such as the participatory will of the people which leads to more interest in collaboration and representation in the political process. Mudamos launched its second major version (2.0) in January 2019, seeking user experience improvements, especially features to make campaigns sharing easier.

Mudamos started using public Blockchain as part of its technical architecture, aiming to create a completely transparent and accountable system for verifying signatures. However, after almost two years, the Mudamos team realizes that the availability of this secure infrastructure where anyone can “look under the hood” does not de facto mean anyone is actually doing so. As with the volunteer lawyers, there is a need to develop an independent, crowdsourced technical governance mechanism to ensure that the system maintains its legitimacy.

Finally, the populist, right-wing president, Jair Bolsonaro elected in 2018, has expressed authoritarian tendencies. It is, thus far not known how changes in politics will impact political culture in Brazil in the near and longer-term. One can surmise that the trend in government toward more autocratic behavior could end up depressing political mobilization and participation. Or, to the contrary, Mudamos may become more popular than ever if it escapes legal challenge.

Conclusion

In many respects, Mudamos -- the app, the process, the model legal framework and the Viradas Legislativas events -- have been an unqualified success. With 700,000 people signing up, participation across the geographic and age spectrum (albeit much gender imbalance) and 800 new bills drafted, it represents a sea change in democratic participation for Brazil. Importantly, the launch of the app reinforced the lesson that merely putting the process online would not be enough to cultivate long atrophied participation skills. If citizens are not used to doing something based on paper, they will not change their behavior to do it digitally. The addition of the volunteer, crowdsourced legal team and the live events for collaborative bill drafting have been instrumental to upgrading the quality and usefulness of participation. At the same time, after a stratospheric launch in the early months, participation is slowing especially as a result of no legislation drafted by the public having yet been enacted. However, the steady use of social and mass media channels is necessary to keep people engaged. Mudamos will need to update its strategy now for the longer-term to turn the idea of “crowd drafting” or direct democratic participation in the drafting of legislation into enacted law. This will require technological improvements, making the app better and introducing better governance mechanisms to enable scrutiny of the program. At the same time, they must invest in participation literacy and continue the work of making people aware of their constitutional right to introduce new legislation as well as educating them about how to do so, especially through grassroots collaboration. Finally, to realize the potential for combining direct with representative democracy, they need to institutionalize these practices by advocating for the recognition of the platform and its practices and the more regularized and systematic monitoring of citizen engagement by Brazil’s legislatures. Maybe then they can aspire, as with participatory budgeting, to have Mudamos in use in every parliament, city council and congress around the world.

Footnotes

[1] TEIXEIRA, L. A. (2008). A Iniciativa Popular de Lei no Contexto do Processo Legislativo: Problemas, Limites e alternativas. 2008: Monografia para Curso de Especialização. Câmara dos Deputados: Centro de Formação, Treinamento e Aperfeiçoamento. Available at: http://bd.camara.gov.br/bd/handle/bdcamara/10190?show=full. p. 9.

[2] The authors list is available on <http://www.camara.gov.br/proposicoesWeb/prop_autores?idProposicao=452953>. Last access on January 18th 2017.

[3] The authors list is available on <http://www.camara.gov.br/proposicoesWeb/fichadetramitacao?idProposicao=2080604>. Last access on January 18th 2017.

[4] See http://fcpamericas.com/english/anti-corruption-compliance/brazils-10-measures-corruption-chamber-deputies-approves-lava-jato-task-force-proposal/.

[6] See <http://www.camara.gov.br/proposicoesWeb/prop_mostrarintegra?codteor=1540249&filename=Tramitacao-PL+4850/2016>.

[7] See <https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=org.mudamos.petition>.

[8] See <https://itunes.apple.com/br/app/mudamos/id1214485690>.

[9] See <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E8PU3zm9oic>.

[10] ALMEIDA, G. de A. (2015) Marco Civil da Internet – Antecedentes, Formulação Colaborativa e Resultados Alcançados. In: Gustavo Artese - Coordenador, Marco Civil da Internet Análise Jurídica Sob uma Perspectiva Empresarial.. São Paulo: Quartier Latin.

[11] Law No. 11419 of 2006 regulates the digitalization of the legal process.

[12] Based on the number of certificates issued in 2018 by the National Certificate Authority of Brazil over a population of 200 million people. Source: https://www.iti.gov.br/ranking-de-emissoes.

[13] See Mozilla Foundation. Introduction to Public-Key Cryptography https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Archive/Security/Introduction_to_Public-Key_Cryptography.

[14] Blockchain is a shared, trusted, public ledger of transactions, that everyone can inspect but which no single user controls. It is a cryptographic, secure, tamper-resistant distributed database. See more: <https://hackernoon.com/blockchain-technology-explained-introduction-meaning-and-applications-edbd6759a2b2>.

[15] See <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fishbowl_(conversation)>.

[16] See Estratégia Brasileira para a Transformação Digital (E-Digital). https://www.governodigital.gov.br/documentos-e-arquivos/estrategiadigital.pdf/at_download/file

[17] Article No. 119 of Rio de Janeiro state Constitution.

[18] Article No. 2 of Brazilian Law 16585 of 2015.

[19] Article No. 98 of Porto Alegre Municipal Organic Law.

[20] BARBOSA, C. Assembleia Legislativa do Estado de Amapá. Pela internet, cidadão poderá ajudar a produzir projetos de lei da Assembleia Legislativa. Available at: http://www.al.ap.gov.br/pagina.php?pg=exibir_not&idnoticia=1545.

[21] See <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brazilian_Institute_of_Geography_and_Statistics>. (11/26/2018). Original source in Portuguese: <ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Populacao/Estimativas_2016/estimativa_dou_2016_20160913.pdf>. (11/26/2018).

[22] See <http://www2.camara.leg.br/atividade-legislativa/discursos-e-notas-taquigraficas/discursos-em-destaque/reforma-politica-1/relatorio-parcial-1-da-reforma-politica>.

[23] See <http://www.camara.gov.br/proposicoesWeb/prop_mostrarintegra;jsessionid=8BE310908A0DBAC8152C6D999F3CA310.proposicoesWebExterno2?codteor=1540588&filename=INC+3228/2017> and <http://www.camara.gov.br/proposicoesWeb/prop_mostrarintegra?codteor=1542795>.

[24] See <https://leismunicipais.com.br/a/pb/j/joao-pessoa/lei-ordinaria/2015/1305/13041/lei-ordinaria-n-13041-2015-disciplina-a-iniciativa-popular-de-leis-a-que-se-refere-o-art-31-da-lei-organica-do-municipio-de-joao-pessoa?q=13041>.

[25] See <https://itsrio.org/iniciativapopular>. (11/24/2018)