Rahvakogu

Turning the e-Republic into an e-Democracy

Read Time

Brief View 9 MINS

Full Story 28 MINS

Briefing Notes

How Does It Work?

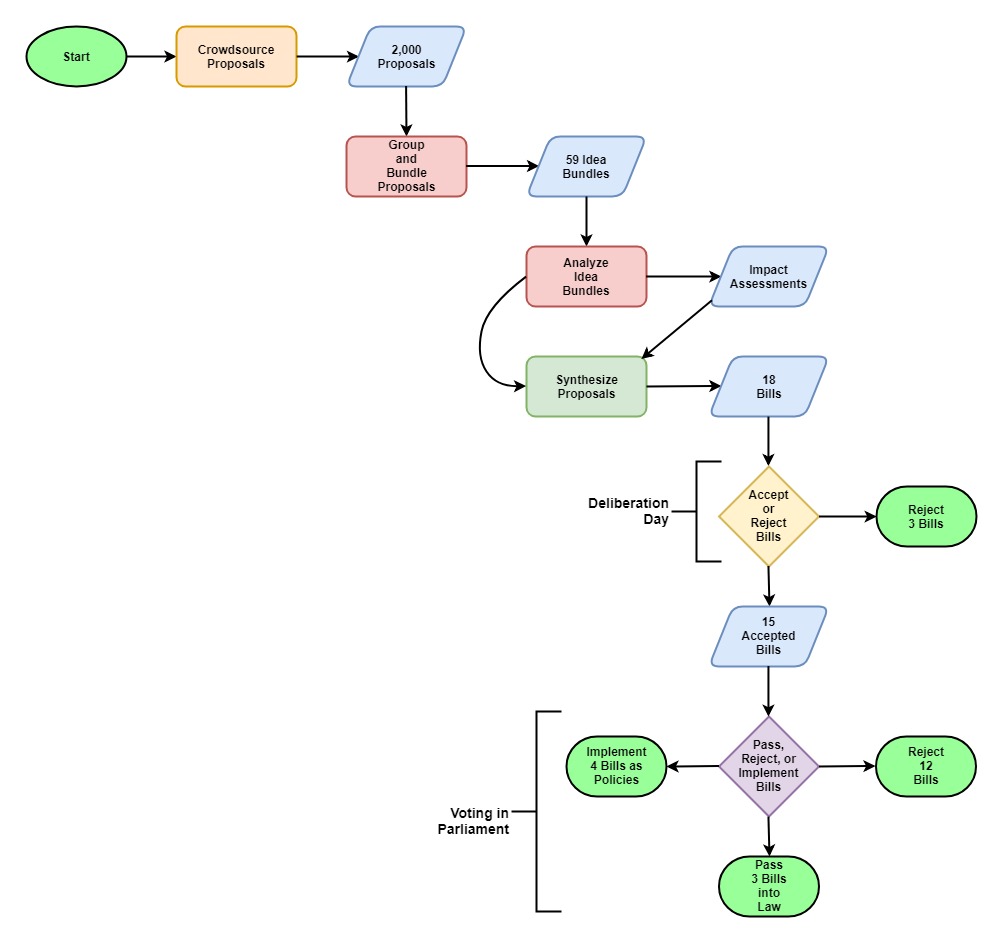

Rahvakogu (The People’s Assembly) was a digital initiative to crowdsource policy proposals for improving the state of democracy and mitigating political corruption in Estonia. Five specific issues (the electoral system, the functioning of political parties, the financing of political parties, public participation in political decision-making, and the politicization of public offices) were selected beforehand as the topics for engagement. Rahvakogu was conducted in four phases: Proposals, Grouping, Synthesis, and Deliberation:

- Proposals - Proposals enabled the public to make policy proposals pertaining to the themes of political reform via the project website, which used the Your Priorities platform developed in 2008 by the Icelandic nonprofit Citizens Foundation for use in the Better Reykjavik project. During the three weeks that the portal was live, from January 7 through January 31, the Rahvakogu webpage garnered over 60,000 views, with over 2,000 users posting 2,000 proposals and 4,000 comments

- Grouping - In February, during the Grouping phase, policy professionals read, summarized, and then grouped the proposals into 59 “bundles.” Then 30 experts in the fields of political science, law, and economics analyzed these bundles and provided an impact assessment of what effect the proposals would have if enacted.

- Synthesis - A series of five seminars were held during the Synthesis phase in March, at which political representatives, experts, and citizens who had submitted proposals in the crowdsourcing process were eligible to participate. Participants then drafted proposals and discussed them in small-group meetings to synthesize their proposals into 18 discrete bills in preparation for the face-to-face Deliberation Day.

- Deliberation - The live Rahvakogu event --the Deliberation Day-- was held on April 6, 2013. The total group of 314 randomly selected and representative citizens were divided into smaller groups of ten to facilitate discussion. Armed with briefing materials prepared by the expert group, and overseen by a moderator, each group deliberated and cast a formal vote to either accept or reject the proposals.

Why is it Interesting

Given its short life span of only a few months, Rahvakogu was one of the most immediately impactful CrowdLaw projects, resulting in legislation that created Rahvaalgatus, a permanent CrowdLaw mechanism for sourcing new policy ideas that is still active today.

What worked

Hybrid approach to use of technology - While policy ideas were submitted through an online platform, the other tasks involved in Rahvakogu, including a Deliberation Day, were done in-person. This allowed the organizers to fill some demographic gaps in participation, and for policy experts and analysts to weigh-in on the submitted policies.

What are the outcomes

In total, 15 of the 18 proposals were accepted by the People’s Assembly, which were then passed along to the Riigikogu (Estonia’s unicameral parliament). Since there was no formal legal mechanism for the Riigikogu to vote on laws drafted by an outside source, the President had to use his power to introduce the 15 bills to parliament. The Riigikogu eventually passed three of the proposals as law, while “four proposals have been partly implemented or redefined as commitments in the government coalition programme.”

What does it cost?

The hosting service for the tool used for Rahvakogu (called YourPriorities) costs $390 per month for medium-sized projects (up to 5000 users) and $2800 per month for large cities/governments (up to 250k users).

What are the benefits?

- The focused and well-defined set of themes (and a process that limited debate only to those topics) ensured that participation remained topical.

- The combination of online, self-selected participation with the selection of an off-line representative sample of the population helped to achieve the best of both diversity and legitimacy.

- The five-stage process that combined public and expert input resulted in actionable and implementable laws and policies.

What are the risks?

- The one-off nature of the experiment and Estonia’s small size (population 1.3 million) means that results may vary.

Introduction

Rahvakogu (“The People’s Assembly”) was a one-off initiative in early 2013 in which Estonian citizens proposed and discussed policy ideas to remedy political corruption via an online crowdsourcing platform and in-person deliberation. The project applied Estonia’s experience of using technology[1] for the delivery of public services to the development of an online crowdsourcing platform[2], which furthered the country’s role as a leader in e-Governance and open government.

The project applied Estonia’s experience of using technology for the delivery of public services to the development of an online crowdsourcing platform, which furthered the country’s role as a leader in e-Governance and open government.

Rahvakogu demonstrates that during the Solution Identification stage of lawmaking, actors outside of the elected government can play a key role in facilitating public engagement in lawmaking, and that this process can happen rapidly through the use of online platforms.

Background

Rahvakogu originated as a reaction by Estonia’s people to perceived corruption in the country’s major political parties following a series of scandals. In December of 2011, the Riigikogu (Estonia’s Parliament) attempted to pass a legislative amendment that would have allocated close to €1 million in public funding to finance political party campaigns- a motion that was widely supported by the major political parties but criticized by civil society. Additionally, early in 2012, protesters targeted the Reform Party and particularly its leader, Prime Minister Andrus Ansip, for the party’s support of the global Anti-Counterfeiting Trade Agreement (ACTA). The most notable scandal, dubbed “Silvergate,” came on the heels of these controversies. In May of 2012, Silver Meikar, a Member of Parliament from the ruling Reform Party, published an article in the Estonian newspaper Postimes detailing an incident in which party leaders instructed him to donate €7,600 from an unknown source to the party, under his own name. Although this is illegal under Estonian law, Meikar claimed that this was a common practice, and that other Reform Party Members had done the same in the past (Praxis, 2014). Though the party denied Meikar’s allegations, and the subsequent investigation yielded nothing due to a lack of evidence, the stage was set for a popular backlash against the party.

This backlash took the form of street protests and rallies, calling for more openness, transparency, and an end to corruption in Estonia’s political system. In November of 2012, 17 activists published Harta 12 (“Charter 12”), an online petition signed by 18,210 people (a large group for a country of only 1.3 million) on the petisioon.ee platform, calling for all Estonian people to establish “a new social contract” between civil society and the government (Karlsson, Jonsson, & Astrom, 2015), one in which:

- The public has an unobstructed view of all revenue sources and political associations

- Parties work in a transparent manner that is in the interest of the people

- Representatives must regularly report to their constituents and act in their interests

- There is a clear, open, and simple path of access to Parliament, and with no monopolization of power

- There are tools other than elections by which citizens can articulate their will

Figure 1: Pro-Charter 12 Protests Source: https://mises.ee/in-english/report-on-estonia/

In response to Harta 12, the then-President of Estonia, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, called a meeting of political scientists, lawyers, political party members, and interest groups, held in an old Jääkelder, or ice-cellar building. It was at this “Ice-Cellar Meeting” that the group agreed on a course of action that included a proposal phase where members of the public could submit policy proposals via an online crowdsourcing platform, and a “Deliberation Day” in which the proposals could be discussed and voted upon. A team spearheaded by the Estonian Cooperation Assembly, and other stakeholders, including the President’s Office, the Praxis Centre for Policy Studies, the Open Estonia Foundation (OEF), the Network of Estonian Non-profit Organizations (NENO), the e-Governance Academy, and IT and communications groups was responsible for actualizing the plan developed during the Ice-Cellar Meeting (Praxis).

The plan developed by the Estonian Cooperation Assembly drew upon the country’s strength at using information technology in the public sphere (Heller, 2017). After gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Estonia oriented its economy around technological innovation. The government created the technological investment fund Tiger Leap Foundation in the early 1990s in part to fund computer programming education in primary schools (Mansel, 2013). Estonians have been able to directly pay taxes online since 2002. In 2001, the state chartered the creation of X-Road, a decentralized database used to store data for over 900 public and private services. In 2002, Estonia introduced a mandatory national identification card that can be used online for electronic banking, healthcare services, signing contracts, and even purchasing public transit tickets (Economist Magazine, 2014). In 2005, Estonia used its electronic ID system to become the first country to allow online voting, which has risen in popularity in subsequent parliamentary and general elections.

Several platforms for electronic citizen participation existed prior to Rahvakogu. One such platform, osale.ee (“Participate”), was created by the State Chancellery of Estonia in 2007 to allow individuals and interests groups to submit policy ideas and consultation about draft legislation.[3] However, not all draft acts are required to be published on the website, and the protocol for whether or not to respond to public submissions is left at the discretion of the ministry involved. While still online as of June 2018, the platform is under-promoted, rarely updated, and “has only a small number of active users” (ECAa, 2017). Another platform, petitsioon.ee, was created by the Estonian Association of Homeowners (a private non-profit) in 2010 as a channel for the public to submit, discuss, and vote in support of proposals on any topic. Though proposals made on this privately-managed forum had no force of law behind them, the platform did host the Harta 12 petition that eventually sparked the Ice-Cellar Meeting and the creation of Rahvakogu.

Mechanics of Rahvakogu

Rahvakogu was conducted in four phases: Proposals, Grouping, Synthesis, and Deliberation. The Proposals phase began in January of 2013 and was hosted online at rahvakogu.ee. The crowdsourcing mechanism was based on Your Priorities, a software platform developed in 2008 by the Icelandic nonprofit Citizens Foundation for use in the Better Reykjavik project.[4] Use of this open-source software allowed the Estonian Cooperation Assembly to quickly roll out the rahvakogu.ee webpage, and to modify the platform to include a digital identification feature and a customized interface (Grimsson, Razgute, & Hinsberg, 2015).

Figure 2: Mechanics of Rahvakogu Flowchart

Proposals had to fall into one of five categories: the electoral system, the functioning of political parties, the financing of political parties, public participation in political decision-making, and the politicization of public offices. Proposals that did not fit into any of these categories were not discussed. This strategy effectively focused the discussion on topics relevant to the issues with the raised in Charter 12: a plurality of proposals dealt with elections (33%) and the funding of political parties (15%) (Liiv, Interview with the author, 2018). During the three weeks that the portal was live, from January 7 through January 31, the Rahvakogu webpage garnered over 60,000 views, with over 2,000 users posting 2,000 proposals and 4,000 comments (Praxis, 2014). Users first had to log in using an electronic ID in order to comment or submit proposals, which made the identity of the user publicly available on the crowdsourcing platform. By one account, this feature helped to “reduce public animosity”, as the vast majority “...of the proposals and comments were..[written] in a neutral tone... some used more colorful language, but it was seldom hostile” (Anonymous Interviewee qtd. In Jonsson, 2015).

Figure 3: Voting on Rahvakogu Proposals

Source: Democracy Day One

In February, during the Grouping phase, the proposals were referred to a group of analysts from the Praxis Center, who divided the five categories into subcategories. Analysts at Praxis (an independent, non-profit, civil initiative think tank) read, summarized, and then grouped the proposals into 59 “bundles” by “applying essentially a methodology similar to grounded theory to find repeating motifs” (Liiv, interview with the author, 2018). In other words, the researchers identified patterns in the data by grouping the unorganized proposals into meaningful categories. The NGOs/Estonian Cooperation Assembly consortium invited a group of 30 experts in the fields of political science, law, and economics to analyze these bundles and to provide an impact assessment of what effect the proposals would have if enacted. While the use of domain experts was a strength of this approach from a data analytics perspective, “the lack of a digital approach to analyzing data can be then seen as the weakness” (Liiv, Interview with the author, 2018), as this behind-closed-doors process led to a lack of transparency in the offline portion of Rahvakogu.[5]

Figure 4: Deliberation Day Meeting

Source: Delfi (see here)

A series of five seminars were held during the Synthesis phase in March, at which political representatives, experts, and citizens who had submitted proposals in the crowdsourcing process were eligible to participate. After considering the expert analyses, seminar participants rated the relevance of the issue bundles, in order “to single out which of the ideas put forward on the online platform could best solve the problems” previously identified (Praxis, 2014). Participants then drafted proposals and discussed them in small-group meetings to synthesize their proposals into 18 discrete bills (Jonsson, 2015), in preparation for the face-to-face Deliberation Day.[6]

The live Rahvakogu event --the Deliberation Day-- was held on April 6, 2013. The total group of 314 randomly selected and representative citizens were divided into smaller groups of ten to facilitate discussion. Armed with briefing materials prepared by the expert group, and overseen by a moderator, each group deliberated and cast a formal vote to either accept or reject the proposals. In total, 15 of the 18 proposals were accepted by the People’s Assembly, which were then passed along to the Riigikogu (Estonia’s unicameral parliament).Since there was no formal legal mechanism for the Riigikogu to vote on laws drafted by an outside source, the President had to use his power to introduce the 15 bills to parliament.

Since there was no formal legal mechanism for the Riigikogu to vote on laws drafted by an outside source, the President had to use his power to introduce the 15 bills to parliament.

The Riigikogu eventually passed three of the proposals as law, while “four proposals have been partly implemented or redefined as commitments in the government coalition programme” (Praxis, 2014) and the other eight were rejected.[7]

Participation

Opportunities to participate varied considerably across the different phases of the Rahvakogu process (See Table 1). During the crowdsourcing stage, everyone was invited to participate in the submission and commenting process. A small group of volunteers with a professional background were involved in the “bundling” and analysis of the proposals. The Deliberation Day discussions and voting opportunities were only open to a representative sample of Estonian citizens who had been randomly selected and invited to participate.

The key statistics of the Rahvakogu online process reveal several striking demographic disparities in participation. One survey found that a significantly larger number of men (+28%, p < .01) than women participated in the crowdsourcing phase; 74% of participants were men, while men make up only 46% of Estonia’s population (Jonsson, 2015). Likewise, crowdsourcing participants were significantly more likely to identify themselves as members of the political left (+5.4%, p<.05) or right (+5.7%, p<.05) rather than the center (-11.1%, p<.01). Compared to the general public, crowdsourcing participants were also more likely to be professionals, non-senior citizens, ethnically Estonian (as opposed to Russian, Estonia’s largest minority group), and to have a higher education (Jonsson, 2015). As a whole, participants were significantly more likely to have some prior experience in political activism, such as having worked in a political party (+4.5%, p<.01), signed a petition (+66.8%, p<.01), or participated in a boycott (+39.8%, p<.01) (Jonsson, 2015). For the Deliberation Day phase, 550 Estonian citizens were invited to participate, comprising a stratified random sample proportionally representing the age, sex, and residence demographics of the Estonian population, of which 314 participated (Praxis, 2014). Compared to Estonia’s population, the group who chose to participate were disproportionately made up of people 56 or older (+18%) and of those with higher level of education (+28%) (Leosk & Trechsel, 2016). All participants were volunteers and received no monetary or reward-based incentives. This may partly explain why participation was in large part limited to citizens with a history of political engagement, as others may not have seen the value in participating.

|

Phase |

Who could participate? |

Who did participate? |

|

Crowdsourcing of Proposals |

Anyone |

Over 2,000 self-selected users. Most were well-educated, politically active Estonian men. |

|

Categorization and Bundling |

Praxis Center Researchers |

Praxis Center Researchers |

|

Analysis and Impact Assessment |

Group of 30 Experts |

Group of 30 Experts |

|

Synthesis Seminars |

Political representatives, experts, and citizens who had submitted proposals in the crowdsourcing process |

Political representatives, experts, and citizens who had submitted proposals in the crowdsourcing process |

|

Deliberation Day |

Randomly-selected, representative, 550-person sample |

Self-selected 314-person sample. Older and more highly educated than general population. |

|

Riigikogu Voting on Proposals |

Members of Parliament |

Members of Parliament |

Table 1: Opportunities for participation by phase

The public was made aware of the People’s Assembly through both official and unofficial mechanisms. The high-profile Reform Party donation scandal received significant media attention, as did the subsequent protests. Charter 12 was also widely circulated in the media (Jonsson, 2015), while the Ice-Cellar Meeting was broadcast online (Praxis, 2014). Each step of the Rahvakogu process was also communicated to the population by Eesti Rahvusringhääling (ERR) --the Estonian Public Broadcasting network-- through a series of online articles from the beginning of the crowdsourcing phase (ERR, 2013a) to the introduction of the proposals to parliament (ERR, 2013b). Deliberation Day was described as a “major media event” which “attracted a great deal of public attention” (Karlsson et al., 2015).

Institutional Description and Impacts

President Ilves’s office organized the Rahvakogu process together with a team of NGO’s and without interference or oversight from the legislature or the political parties. The organizational structure was built upon the existing structures of the Estonian Cooperation Assembly, the Praxis Centre for Policy Studies, the President’s Office, and the other interest groups involved. These were each independent groups with various sources of funding. Primary funding was provided by the Estonian Cooperation Assembly (Hellam, Interview with the author, 2018), which itself is a network of 77 non-governmental organizations (NGOs) funded by the Estonian Government, and was established in 2007 by President Ilves to research long-term national policy recommendations. Each group took custody of one aspect of the project. The ECA was responsible for the design and management of the rahvakogu.ee portal, while the Praxis Center processed and analyzed the data submitted through the portal. OEF designed the Deliberation Day based on James Fishkin’s model for a Deliberative Democracy (See Footnote 6). Network of Estonian Nonprofit Organizations (NENO) managed the Deliberation Day event, while Open Estonia Foundation (OEF) covered the operating costs via a €50,000 grant (OEF, 2013; Hellam, Interview with the author, 2018). Several of the other individuals involved, such as the experts panel, were unpaid volunteers (Jonsson, 2015). As Rahvakogu was an ad hoc effort that was not fully planned in advance, none of the participants or organizers received training prior to their work (Leosk, Interview with the author, 2018).

One of the adopted proposals in the 2012 process created Rahvaalgatus, a permanent mechanism by which Estonian citizens can propose and vote on policy changes (See “Mechanics of Raahvalgatus”). A second proposal lowered the required number of members to establish a political party to 500, a compromise between the People’s Assembly’s 200-member suggestion and the prior 1,000-member threshold. This legislation resulted in the creation of a new political party, Vabaerakond (“Free Party”), which formed with 650 members in 2014, and won eight seats in the 2015 Riigikogu elections (Leosk and Trechsel 2016). Another compromise reduced by half the deposit required to run for election in the Riigikogu, in place of the People’s Assembly’s suggestion to replace the monetary deposit with supporters’ signatures (Grimsson et al., 2015). In addition to these tangible changes, the overall impact of the process was the stabilization of the political climate and the easing of tensions in Estonia (Leosk, interview with the author, 2018).

Mechanics of Rahvaalgatus

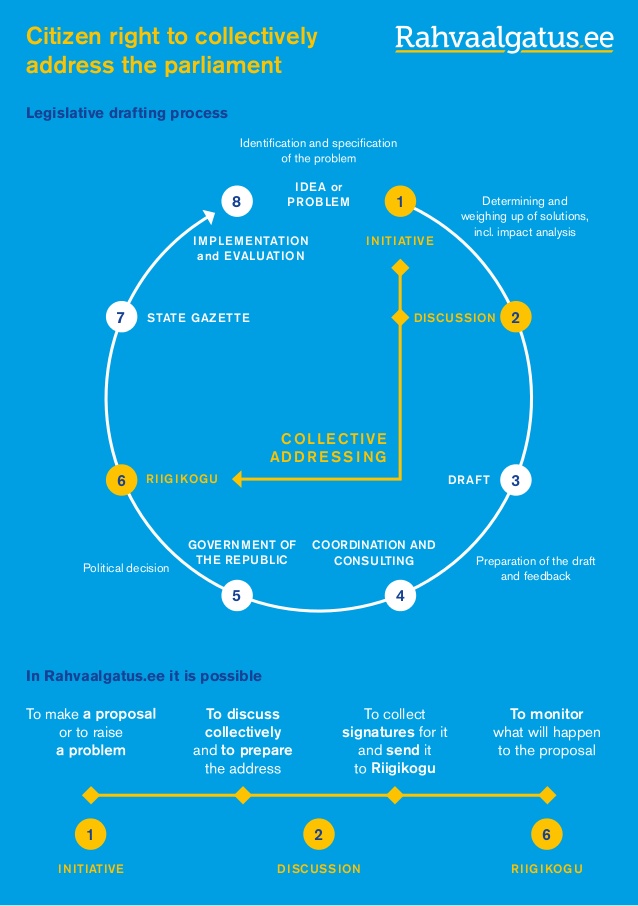

Since the process was tried only once, Rahvakogu did not have the opportunity to adapt or to iterate using its experiences. However, some lessons learned were incorporated into the Rahvaalgatus (“Citizen’s Initiative”) platform. Hosted on the Estonian open-source CitizensOS platform (a non-profit project created by the Let’s Do It! organization and funded through the Open Estonia Foundation) since March of 2016, Rahvaalgatus is the channel by which citizens can directly petition the Riigikogu. Rahvaalgatus allows citizens to create or co-create “Collective Addresses”, or policy proposals. Unlike Rahvakogu, Rahvaalgatus proposals do not need to fall into any pre-defined category.[8] Users submit proposals with an up to three page explanation of

the current problem and how the Address would rectify it --eliminating the need for an outside group to bundle and draft legislation. Other users are then able to comment on

Figure 5: Rahvaalgatus.ee homepage, with in-progress proposals

and discuss the proposals. Estonian residents who are least 16 years old can then digitally sign proposals using their full name and electronic ID number, or a Google or Facebook account (the preferred forms of login for many young people) (Leosk, Interview with the author, 2018). Proposals that receive 1,000 signatures are then transferred to the Board of Riigikogu, a body elected by and consisting of parliament members, which then has 30 days to decide whether or not the proposal will proceed. The Board refers accepted proposals to a relevant Riigikogu Committee, which must discuss the proposal within three months; the Committee must also invite the creator of the Address to represent the proposal during at least one Committee meeting. Within six months, the Committee must decide to accept, partially accept, or reject the Address. If the proposal is accepted, the Committee may address the issue raised by drafting legislation, calling a public hearing, forwarding the Address to a relevant governmental or non-governmental institution, or by finding “an alternative way” to solve the problem. At each stage, the acting body must inform the creators of the status of their Address, and if it is rejected, the reason for its rejection (Rahvalgatus.ee, 2016). Rahvaalgatus minimizes the burden that the right to direct petitioning could otherwise have on Members of Parliament, as it acts as a centralized replacement to the myriad official and unofficial petitioning platforms that existed prior to Rahvakogu.

Rahvaalgatus minimizes the burden that the right to direct petitioning could otherwise have on Members of Parliament, as it acts as a centralized replacement to the myriad official and unofficial petitioning platforms that existed prior to Rahvakogu.

This prevents MPs from being inundated by petitions from various sources. The 1,000 signature threshold acts as a filter that selects only the most relevant and compelling proposals and sifts out the others, which prevents MPs from being overloaded with information. Parliament is also not obligated to discuss proposals that are clearly out of line Estonia’s constitution, or that repeat the same topic as another Address that was discussed within a two-year time span. The commenting and voting mechanic allows for an automated, informal public consultation procedure from the very beginning of the lawmaking process. By receiving Collective Addresses, MPs can easily remain up-to-date on the issues that are most relevant to Estonian citizens. As these processes are largely automated on the Rahvaalgatus.ee platform, which itself is operated by the ECA, the workload allocated to Riigikogu Members is minimal. At the same time, the MPs ultimately retain control over which policy ideas are implemented and how this is done.

While the right to petition parliament was established in Estonia’s Constitution, the second Rahvakogu proposal submitted to and passed by the Riigikogu in 2014 as the “Response to Memoranda and Requests for Explanations and Submission of Collective Addresses Act” established the 1,000 signature threshold and other rules for petitioning. The Estonian Cooperation Assembly worked also with the creators of ManaBalss.lv (“MyVoice”), a similar platform in place in Latvia since 2011, to design the new platform (Hellam, Interview with the author, 2018). Like ManaBalss, the new platform incorporates such features as an electronic ID authentication system and a signature threshold that proposals much reach in order to advance[9]. As of May 2018, the website has attracted an average of 10,000 visitors per month, with engagement on the platform growing from 2016 to 2017 (ECA & Chancellery, 2018).

Figure 6: Process of drafting a bill through Rahvaalgatus.

Source: Rahvaalgatus One pager

Risks and Challenges

There were several challenges that the organizers of Rahvakogu had to overcome. In a lecture at the Open Government Partnership Summit in 2013, Urmo Kübar, head of the Network of Estonian Nonprofit Organizations during the Rahvakogu initiative, noted that the greatest challenge the project had to overcome was skepticism (OGP, 2013). Some skeptics were apprehensive about opening up the lawmaking process to anyone, regardless of their educational background or professional experience. Mall Hellam, Director of the Open Estonia Foundation, added that some skepticism about the Rahvakogu and Rahvaalgatus was expressed by the media (Interview with the author, 2018). An additional challenge from the initiative’s onset was the fairly volatile political climate resulting from the Silver Meikar incident, in which there was a great deal of hostility directed toward Estonia’s political parties by the electorate.

In this sense, there was also the added risk that the People’s Assembly could be insufficient in meeting the reforms demanded by the people. Much of this risk hinged on the relationship (or lack thereof) between the People’s Assembly and the Riigikogu, as the parliament could have rejected all of the proposals it heard, which in addition to nullifying the work done by the NGOs and volunteers involved with Rahvakogu, could have created more hostility toward the parties and the legislature.

These risks and challenges were partially overcome through a strategy led by the President and Estonian Cooperation Assembly rather than the legislature, with minimal input from the major political parties. As the President of Estonia is largely a figurehead position with no executive power, and since the public generally has a higher level of trust in the President’s Office than in the Government as whole, this leadership strategy minimized the backlash that otherwise may have derailed the initiative (Karlsson et al., 2015). This strategy was not without criticism, however, as some in the media argued that a government-involved process could not succeed, and objected to the use of public funds.[10] Still others argued that the Rahvakogu initiative did not go far enough, and should have been institutionalized as a permanent system. This, however, was not feasible, as after the project’s completion, there was little funding or political will to keep the project going (Hellam, Interview with the author, 2018).

As Rahvakogu relied on technology only for the proposal stage and was able to use an open-source platform, there were few technological constraints. The one-time nature of the project enabled several of the strategies to be used that would be not be economically or politically feasible in the long-term, since the project relied on a substantial amount of labor-intensive pro bono work to transform the raw proposals submitted by the people into something useable by the legislature. Perhaps the most significant constraint on the project was time, as the project was rolled out very quickly in order to address the civil unrest brewing at the end of 2013; this accounts for the short timespan allocated to the crowdsourcing phase. Legally, the project operated in a gray area; while there was no explicit provision for civilians to propose or introduce policy changes to the Riigikogu, there was no law preventing it either.

While many of Rahvakogu’s issues were addressed with the creation of Raahvalgatus in 2016, some others persist. The nature of the Rahvakogu project left much of the discretion in the hands of the Riigikogu (a lingering issue with Rahvaalgatus), which largely chose to reject the proposals that would have curbed many of the powers and privileges of its members. For instance, parliament rejected one proposal which would have prohibited legislators from serving in both the national government and in local councils, and another which would have created a procedure for voting on certain bills in public referenda. Similarly, the Rahvaalgatus mechanism leaves the ultimate fate of proposals up to one or more Riigikogu commissions. This makes it somewhat difficult to measure the impact of the platform, as even accepted proposals do not necessarily result in direct legislation.

Reactions

Many consider Rahvakogu to be a successful project with room for improvement (Liiv, interview with the author, 2018; Hellam, interview with the author, 2018). Mall Hellam states that Rahvakogu was successful as a one-time project, but that the project lacked the attention or political will to continue long-term. Also, serious effort has to be made to give better civic education in schools, as well as offering funding opportunities for organizations in the NGO sector who aim to educate people about different forms and methods of modern democracy. Similarly, Dr. Innar Liiv, Associate Professor of Data Science at Tallinn University of Technology, sees the initiative as a success due to the role played by the President and questions whether the project could have worked without the President’s involvement (Interview with the author, 2018). Nele Leosk, CEO and Senior Digital Governance Expert at International Governance Leadership, sees the project’s timing as an additional strength, as the well-timed initiative captured the attention of potential participants and the media. The country’s history of public participation online, readied its people to participate in Rahvakogu (Leosk, Interview with the author, 2018).

Other commentators were more critical. In a Postimees interview, MP Jüri Adams compared the People’s Assembly to a lucky game of Russian Roulette which could have unraveled Estonia’s parliamentary democracy, arguing that the project’s “unusually sensible result” would likely not be repeated if the project were tried again (Esle, 2013).

Several experts also identified areas of improvement. One weakness of the project was that the platform disproportionately drew upon the opinions of young, professional Estonian men rather than the “crowd” as whole. Nele Leosk notes that for projects like Rahvakogu, often one means of participation is not sufficient, because different demographic groups prefer to participate in different ways. As crowdsourcing primarily attracts a certain type of person, other methods should be considered if the goal is to reach a wider range of people (Interview with the author, 2018). On the other hand, Mall Hellam, Director of the Open Estonia Foundation, contends that similar projects in the future do not necessarily need to involve or be marketed toward the whole population, as not everyone will want to join; it is more important to engage the proper stakeholders, even if these groups are not the most visible. This requires finding an adequate source of funding to properly develop the platform and a strategy to effectively communicate the platform to stakeholders (Interview with the author, 2018).

The entire Rahvakogu process was intended to be transparent, with the entire population invited to participate, and with each step of the process explained via public media. However, Leosk notes that transparency in decision-making was lacking at some stages. For instance, the criteria or methodology on which the proposals that were debated during Deliberation Day were chosen, and how exactly these proposals were agreed upon, remains unclear. This ambiguity is partly a result of Rahvakogu’s unplanned nature (Interview with the author, 2018).

An additional weakness was that Rahvakogu was unsuccessful in restoring trust in Estonia’s institutions, at least among its participants. A survey of Rahvakogu participants found that 65% experienced a decrease in trust in the government, political parties and parliament, while only 10% increased their trust. By contrast, 40% of respondents increased their trust in their fellow citizens, while only 13% experienced a decrease in trust. Notably, participants who had higher levels of satisfaction in Estonia’s democracy were significantly more likely to experience an increase in institutional satisfaction. Additionally, participants that gained trust in institutions were less likely to gain trust in civil society, and vice versa (Karlsson et al., 2015). This indicates that Rahvakogu has done little to ease the dissatisfaction that some Estonians feel with their government.

Though, when put into the Estonian context, these findings are somewhat dubious. Dr. Innar Liiv remarks that Estonians experienced extraordinarily high levels of trust in government after re-gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. As such, Estonians’ trust in government will continue to decline naturally as it “converges” with lower levels of trust in the rest of the world (Liiv, interview with the author, 2018). An additional consideration is that Rahvakogu participants were not a representative sample of Estonia’s population, and so these result may not be generalizable to Estonia’s wider population. Anecdotally, some say that Rahvakogu improved the political situation and smoothened the relationship between the government and civic society (Leosk, Interview with the author, 2018). Indeed, according to data from the biyearly European Social Survey, the percentage of Estonians with lower-end levels of trust[11] in their country’s parliament dropped from 55.3% in 2012 to 48% in 2014.[12] Though, as this decrease in low trust continued, dropping to 43.8% in 2016 (well after the end of Rahvakogu but before the launch of Rahvaalgatus) the improvement cannot directly be attributed to the People’s Assembly.

When describing Rahvaalgatus in February of 2018, Estonian Cooperation Assembly Director Teele Pehk stated that the site has a “user-friendly approach supported with systemic work with (potential) users and stakeholders responsible for inter-linked processes”, and called it the “forerunner of (e-)democracy in Estonia”. Though, Pehk concluded that “30+ collective addresses [submitted through Rahvaalgatus] have not had a measurable impact on how the Estonian society is being governed or problems solved” (2017). Pehk also described a “vicious circle of distrust” that continues to hinder public participation on the Rahvaalgatus platform (2018). Likewise, Mall Hellam observed that while the Rahvaalgatus website works well, it is not very well publicized by the media or by Estonia’s politicians (Interview with the author, 2018).

Key Learnings

Despite its shortcomings, Rahvakogu is most a relevant CrowdLaw exemplar because of its key features: a hybrid online and offline approach and rigorous focus on a single area of policy. The adoption of an existing, tested Icelandic crowdsourcing platform allowed the organizers of Rahvakogu to quickly roll out the Rahvakogu web page and to modify it to better suit their purposes. The use of predefined categories on the platform indicates that limiting proposals to a certain set of topics successfully focused the debate on identify solutions to key issues. However, a complementary offline component was also necessary to fill the gaps in participation; as crowdsourcing platforms tend to be used disproportionately by young, well-educated, politically active men, a portion of the process where participation is assigned through random representative sampling can allow for a sample that better represents a country’s population. The offline process also allowed for consultation by experts, analysts, and political representatives to ensure that proposals were high-quality and high-impact. In future projects, offline involvement should be done in as transparent a manner as possible.

Although non-governmental organizations and the executive branch rather than the legislative branch led the Rahvakogu effort, the creation of the institutionalized CrowdLaw mechanism Rahvaalgatus ultimately benefited Parliament. Through Rahvaalgatus, Members of Parliament continue to benefit from a institutionalized, centralized, and curated stream of policy ideas which prevents an overload of information, and allows MPs to remain current on the issues that are most relevant to their constituency. From an institutional perspective, actors outside of the elected government can play a key role in facilitating public engagement in lawmaking.

Interviews

Hellam, M. (2018, June 26). Video call interview with D. Gambrell and A. Dinesh

Leosk, N. (2018, June 28). Video call interview with D. Gambrell and V. Alsina

Liiv, I. (2018, July 1). Email interview.

Footnotes

Ackerman, B., & Fishkin, J. S. (2004). Deliberation Day. New Haven, United States: Yale University Press.

Allan, S. (2013). Estonia. European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook, 52(1), 61-64. doi:doi:10.1111/2047-8852.12008.

Derlos, M. . (2017, 12 June 2018). Co-creation in policy-making and everyday-democracy. [Online Slideshow] Retrieved from http://www.civicspace.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Estonian-Cooperation-Assembly-Maria-Derl%C3%B5%C5%A1-Crowdsourcing-method-.pdf

Economist Magazine. (2014). Estonia takes the plunge: A national identity scheme goes global. The Economist,. Retrieved from: https://www.economist.com/international/2014/06/28/estonia-takes-the-plunge

ERR. (2013a). NGOs Launch Crowd-Sourcing Project to Repair Democracy. ERR News. Retrieved from: https://news.err.ee/106124/ngos-launch-crowd-sourcing-project-to-repair-democracy

ERR. (2013b). Sweeping Political Financing and Oversight Bill to Take the Floor. ERR News. Retrieved from: https://news.err.ee/107357/sweeping-political-financing-and-oversight-bill-to-take-the-floor

Esle, U. (2013) "Jüri Adams: The People's Assembly is like a Russian Roulette." [Estonian, translated by Google] Postimees. Retrieved from https://arvamus.postimees.ee/1203914/juri-adams-rahvakogu-on-nagu-vene-rulett

Estonian Cooperation Assembly. (2017, 5 January). New year activities of Assembly of Cooperation. Retrieved from https://www.kogu.ee/en/new-yesr-activities-of-assembly-of-cooperation/

Estonian Cooperation Assembly (2017, 13 January). Is it an illusion? A participatory website allows ordinary people to participate in state government. Retrieved from https://www.kogu.ee/en/is-it-an-illusion-a-participatory-website-allows-ordinary-people-to-participate-in-state-government/.

Estonian Cooperation Assembly & Chancellery of Estonia (2018). Citizen initiatives platform Rahvaalgatus.ee in numbers since 2016 [Online Slideshow]. Rahvaalgatus.ee. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1ZRe7LhQT-Y7q_aSX-NubuSNCjQbY2iGr9Th3uYVMOv8/edit#slide=id.g371535d992_0_0

Grimsson, G. and Bjarnson, R. (2015). Priorities of the people: an interview with Iceland's Citizens Foundation. England, P. openDemocracyUK. Retrieved from https://www.opendemocracy.net/ourkingdom/phil-england/priorities-of-people-interview-with-citizens-foundation

Grimsson, G., Razgute, G., & Hinsberg, H. (2015). Rahvakogu - How the people changed the laws of Estonia. Retrieved from: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1lhoyZfRsgfhQkcSppu3L78_Uz_IugUkzMycN2xg3MPo/edit#heading=h.ckyzc8dp16y9

Heller, N. (2017). Estonia, the Digital Republic. The New Yorker, (December 18 & 25, 2017). Retrieved from: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/12/18/estonia-the-digital-republic

Jonsson, M. E. (2015). Democratic Innovations in Deliberative Systems - The Case of the Estonian Citizens' Assembly Process. Journal of Public Deliberation, 11(1), 1-29.

Karlsson, M., Jonsson, M. E., & Astrom, J. (2015). Did the Estonian Citizens’ assembly help restore political legitimacy?: Analyzing changes in vertical and horizontal trust among participants. (Paper prepared for presentation at the ECPR General Conference in Montreal 2015.). Montreal. Retrieved from: https://ecpr.eu/Filestore/PaperProposal/c42dbab9-77b1-406f-a696-bebf9c7ef2e3.pdf

Leosk, N. and A. H. Trechsel (2016). Beyond digital crowdsourcing - how the Estonian People’s Assembly solved a crisis of democracy [Online Slideshow]. Impacts of Civic Technology Conference, Barcelona, European University Institute. Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/mysociety/beyond-digital-crowdsourcing-how-the-estonian-peoples-assembly-solved-a-crisis-of-democracy

Mansel, T. (2013). How Estonia became E-stonia. BBC News. Retrieved from bbc.com/news website: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-22317297

OEF. (2013). Open Estonia Foundation 2013: Implemented and supported projects. Retrieved from: https://oef.org.ee/fileadmin/media/valjaanded/uuringud/AEF-aastaraamat-2013_ENG.pdf

OGP (Producer). (2013, 7 June 2018). #OGP13 Summit Bright Spots: Urmo Kübar, NENO, Estonia. OGP 2013 Summit Brightspots. [YouTube Video] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MF0an6P690I

Pehk, T. (2018). "Rahvaalgatus.ee – yet another e-platform for civic engagement? No, a process of democratic renewal instead!". Open Government Partnership. Retrieved from https://www.opengovpartnership.org/stories/rahvaalgatusee-yet-another-e-platform-civic-engagement-no-process-of-democratic-renewal 2018.

Praxis Center for Policy Research (2014). People’s Assembly in Estonia – crowdsourcing solutions for problems in political legitimacy. Retrieved from https://www.kogu.ee/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Peoples-assembly_summary-by-Praxis_2014.pdf

Rahvalgatus.ee. (2016). What is collective addresses and rahvaalgatus.ee [sic]? Estonian Cooperation Assembly & Chancellery of the Riigikogu. Retrieved from https://www.kogu.ee/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Rahvaalgatuse-voldik_ENG.pdf

[1] See Nathan Heller’s (2017) article “Estonia, The Digital Republic” in The New Yorker.

[2] The platform was built upon an existing open-source Icelandic platform (See “Mechanics of Rahvakogu”).

[3] The osale.ee platform replaced the earlier Täna Otsustan Mina (“Today I Decide”, or TOM) platform, which was created by the Estonian Government in 2001. TOM was a stand-alone platform that allowed citizens to propose, discuss and vote on policy ideas. In contrast to TOM, osale.ee is coordinated with Estonia’s Electronic Coordination System for Draft Legislation (EIS), a database that hosts draft legislation and supporting documents for public view and coordination between government agencies. In 2008, a consortium led by the e-Governance Academy, State Chancellery of the Republic of Estonia and the European Union Democracy Observatory spun off the TOM into the open-source TID+ platform, with the intention of disseminating the e-participation tool to governments and NGOs in the European Union and beyond.

[4] The Better Reykjavik experience served as proof-of-concept for the platform (Grimsson & Bjarnson, 2015), and as a source of inspiration for the organizers of Rahvakogu (Jonsson, 2015). Any user can register for a Your Priorities account using either email or Facebook, and then can create a community with various groups within it. The platform allows for customization, such as whether or not to allow voting, to allow only certain users to propose ideas, to define the timespan for voting on ideas, and to designate users as moderators. As the platform is free and open-source, further customization can be done by downloading the source code from the application’s GitHub page.

[5] The details of this portion of the process remain somewhat hazy. Who selected these experts and the methodology the experts used to analyze the proposals is unclear.

[6] The term refers to Bruce Ackerman’s and James Fishkin’s (2004) book of the same name, in which the authors propose changes to the American political system to remedy the problems of lackluster civic engagement, the commodification of political campaigns, the failures of campaign finance reform. The keynote proposal of the book is Deliberation Day, which the authors describe as a two-day civic holiday held two weeks before the national election, where voters are invited to take part in small and large group meetings about central campaign issues, in order to foster “a more attentive and informed public” (Ackerman & Fishkin, 2004, p.3).

[7] As articulated by Grimmson, Razgute, and Hinsberg (2015) of the Citizens Foundation, the submitted proposals were:

- Regulate the process of informing the public and participating in the legislative process.*

- Legalisation of citizen initiatives (petitions).†

- Facilitate the procedure for holding a referendum for legislative proposals and other issues of public life.*

- Change the way political parties are financed in such a manner that 50% of the money is divided equally between all parties that exceed the threshold and 50% between all parties that participate in elections depending on the number of votes they received.‡

- Criminalise illegitimate donations to political parties.‡

- Expand the power of the authority or committee that supervises the financing of political parties to check all of the economic activities of the parties financed by the state and their affiliate organisations.‡

- Prohibit members of the Riigikogu from being members of the supervisory boards of public enterprises.*

- Establish the legal liability of the supervisory board members of public and municipal enterprises.*

- Allow for a political party to be founded with 200 members, instead of 1,000.†

- Establish a maximum limit for the volume and/or cost of political advertising.*

- Replace the election deposit with supporters' signatures.†

- Lower the threshold in Riigikogu elections from five to three per cent to get a party into parliament.*

- Distribute a compensation mandate on the basis of the number of votes given to the candidate.*

- Grant a mandate to an independent candidate on the condition that they collect at least 75% of the district's simple quota.‡

- Stipulate that elected candidates are obliged to start working in the selected position, define list of permitted exceptions.*

*= Rejected

†= Passed into law

‡= Adopted as policy or policy commitment

[8] Rahvalgaatus proposals thus far have followed two major themes: environmentalism and public health. Of the 18 proposals that have been submitted to the parliamentary committees as of May 2018, the majority were handled by the Environmental Committee (n=6) and the Social Affairs Committee (n=4). Environmental proposals submitted to the Riigikogu have ranged from the protection of the habitat of flying squirrels, to the banning of the glyphosate herbicide, to the preservation of the Väike väin strait ecosystem (ECA, 2017). In early 2017, the ECA invited citizens to submit proposals aimed at solving future problems that will be caused by Estonia’s aging population, particularly access to health insurance and the diminishing funds of the country’s pension system (Derlos, 2017). Another high-profile proposal submitted to the Riigikogu aimed to decriminalize cannabis possession and legalize medical marijuana (ECA, 2017).

[9] Despite the countries’ similar population sizes (Latvia has only about 600,000 more people than Estonia), the threshold for a proposal to advance on Latvia’s platform is 10,000 signatures, significantly higher than Estonia’s 1,000 signature threshold.

[10] Although the ECA functions like an NGO, the association was founded by Fmr. President Ilves in 2007, and receives public funding via the President’s Office.

[11] ESS presents this question as a Likert scale ranging from zero to 10, where zero is “no trust” and 10 is “complete trust”. “Lower-end” refers to a score of four or lower.

[12] Data were tabulated and weighted using the Norwegian Social Science Data Services online data tool on the ESS website. These data were weighted using the “post-stratification weight including design weight” option, as per the ESS guide on weighting data.