Social Auditing

People-Led Evaluation (Promise Tracker, Brazil, TransGov, Ghana and City Scan, USA)

MethodSocial auditing

Participatory TaskIdeas, Actions

Read Time

Brief View 7 MINS

Full Story 23 MINS

Briefing Notes

How Does It Work?

The Internet creates the opportunity for asking the public how to measure impact of laws and policies, what data to use for that purpose and enlisting people in the process of evidence gathering to support better evaluation and oversight. Such participation has the potential to enhance accountability and improve results. Although only one of these social auditing projects involves the legislative branch of government, the success of these initiatives, coupled with the absence of many legislative examples (UK Evidence Checks and Chile’s Evaluación de Leyes are two notable exception), leads us to include them as worthy exemplars for legislatures looking to engage the public in oversight and evaluation.

Platforms

- The Promise Tracker Tool - https://monitor.promisetracker.org/

- TransGov - https://www.transgovgh.org/

- Casio Pocket PCs, Digital Cameras

Projeto Controladoria na Escola involved asking students to collect data about their local school environments, report the major issues they faced, identify the root causes of those issues and propose ideas to fix them, initially by hand, and then using the Promise Tracker tool. In the pilot phase students from 10 schools identified over 600 issues such as burnt out light bulbs, missing fire extinguishers and broken chairs. The Comptroller General visited each school later that year to monitor the results of the project and to oversee the resolution of the issues.

TransGov- Created in 2014, TransGov is a platform to help Ghanaian citizens monitor the progress of local development projects. The creators of TransGov (Jerry Akanyi-King, Kennedy Anyinatoe, Kwame Yeboah and Prince Anim) found that citizens were unaware of whom to hold accountable for faulty or incomplete infrastructure projects (such as the construction of public schools and flyovers) and service delivery in their localities. The solution they developed was “to curate a list of development projects in local communities and give people the ability to comment, give feedback and let their voices be heard.” The platform also allows people to report issues such as birst pipelines or potholes and track the status of their complaint.

CPEC CityScan - In 2000, the Connecticut Policy and Economic Council (CPEC) conducted a pilot project to engage local residents in collecting data to evaluate public projects in order to hold the local government accountable for its commitments to clean up derelict land use sites and advocate for change. The project, called CityScan, involved providing ordinary citizens in Hartford, Connecticut, and later in half a dozen other cities in the state, with what was, at the time, state-of-the-art technology including handheld computers, wireless modems and first-generation digital cameras and training them to collect data to assess the performance of government agencies and hold them accountable. This “social auditing” effort was part of a broader initiative by the Council to introduce citizen-based performance assessment (CBPA) in local neighborhoods and eventually statewide, making CityScan one of the earliest examples of technology-enabled social auditing anywhere in the world.

What are the outcomes?

Projeto Controladoria na Escola- In one school alone, the students identified 115 issues and within just 3 months, 45% of the issues were fixed either by the department of education or, where possible, by the students and school management themselves. More recently, 4,000 students from 104 public schools participated in the campaign and helped evaluate the state of classrooms, availability of Wi-Fi and computer labs, toilet paper in bathrooms and other issues by collecting evidence in response to a questionnaire administered through Promise Tracker. Now the project is expanding to 200 schools.

TransGov- Today, TransGov has 600,000 registered users who provide feedback through the TransGov website, mobile app, by SMS or by phone.. By posting complaints received on TransGov to social media sites, the time taken to resolve complaints reduced by nearly 60% since public officials were subjected to the heightened scrutiny. On average it takes 3 days to fix a pothole and 48 hours to fix a burst pipe reported via TransGov compared with nearly a week to fix a pothole and more than 3 days to fix a pipe before TransGov’s social auditing process.

CPEC CityScan- In Hartford, CityScan played an important role in enabling other organizations to improve their own work. The most prominent example of such an organization was “Hartford Proud & Beautiful,” a private-public partnership which worked towards clearing graffiti from public sites. They used data about graffiti in public spaces in 90 sites in Hartford collected by CityScan volunteers to clean the graffiti. Following the success of the two pilots in Parkville, CityScan expanded to eighteen more neighborhoods in Hartford and eventually, to seven more cities in Connecticut.

What are the benefits?

- Whether in the US, Ghana or Brazil, using a distributed community network made it possible for government and civil society to get a clearer picture of on-the-ground conditions,

- Using digital cameras, smartphones and other tools, they often created an actual picture or even video of conditions that could be used to hold institutions to account.

- Cooperation between the network of volunteers and government institutions is crucial for impact. CPEC got local governments to commit to the clean-up of derelict land-use sites and volunteers, using hand-held devices were able to take the pictures needed to hold them to account.

What are the risks?

- Social auditing needs to be tied to measurable outcomes, such as increasing the number of problems fixed in schools or derelict land use sites to be cleaned up. Without clear outcomes, the project will fail.

- The “crowd” volunteering to participate in social auditing needs to understand clearly what is being asked of it.

- Without an institutional actor ready to respond, the efforts of the social auditing community will not lead to outcomes.

Introduction

Policy evaluation is the process of “understanding how a policy or other intervention was implemented, what effects it had, for whom, how and why.”[1] It serves as an important piece in the feedback loop to improve existing service delivery and inform future policy formulation. However, some of the oft-cited challenges to effective evaluation include scarcity of resources and access to relevant data.[2] The Internet creates the opportunity for engagement by asking the public how to measure impact, what data to use for that purpose and enlisting people in the process of evidence gathering to support better evaluation and oversight. Such participation has the potential to enhance accountability and improve results.

The Internet creates the opportunity for engagement by asking the public how to measure impact, what data to use for that purpose and enlisting people in the process of evidence gathering to support better evaluation and oversight. Such participation has the potential to enhance accountability and improve results.

Below, we summarize three so-called social auditing (also called civic auditing) initiatives that have enabled greater citizen participation in monitoring government projects. Although only one of these involves the legislative branch of government, the success of these projects, coupled with the absence of many legislative examples (UK Evidence Checks and Chile’s Evaluación de Leyes are two notable exception), leads us to include them as worthy exemplars for legislatures looking to engage the public in oversight and evaluation.[3]

Student-led Civic Audits in Brazil

In late 2016, at an event to mark the launch of a new Brazilian government transparency portal, the director of a high school from the rural area of Gama, Brazil publicly rued the severe lack of resources dedicated by the government to his institution - a story that is not uncommon in Brazilian public schools:

“I bought the taps installed in the bathrooms. I turned my living room into a pantry for food. I am very sad about this situation” - Edgard Vasconcelos, director of CED Casa Grande

A decree passed in 2007 ensures that Brazil’s public schools have the autonomy needed to spend funds assigned to them by the federal district for maintaining and operating the school. The intention behind the decree (called Programa de Descentralização Administrativa e Financeira (PDAF)) was to help public school management respond in an agile manner to local needs, which they are best-suited to know.

Between 2007, when the decree was passed, and 2016, over R$ 445 million was provided to public schools for school maintenance and local repairs with R$ 84 million being provided in the year 2016 alone. Despite this, audits conducted in random municipalities by the nation’s Comptroller have shown that there are deficiencies in school infrastructure quality across the country. Studies have attributed these deficiencies to several causes, including lack of resources, corruption[4] and student behavior, but there is less information available at granular levels to pinpoint issues such as those faced by the Casa Grande high school in Gama. School administrators have often complained that they are constrained by delays in funding transfers while government officials have passed the blame back to schools.

In 2016, the Comptroller General of the Federal District (CGDF) launched an initiative called the Projeto Controladoria na Escola (Controllership in Schools) to engage students in 10 public schools in Brazil in the process of auditing school infrastructure, mapping commonly raised issues and fostering civic education in schools.[5]

The initiative was in accordance with the National Social Participation Policy (PNPS) that aims to prevent corruption by ensuring that public resources are spent transparently and with effective participation of society. It was also one of the 22 projects[6] selected from over 90 proposals submitted to the #TodosJuntosContraCorrupcao campaign, a national anti-corruption campaign by the “ENCCLA”, the National Strategy to Combat Corruption and Money Laundering.[7]

Pilot Phase

Projeto Controladoria na Escola involved asking students to collect data about their local school environments, report the major issues they faced, identify the root causes of those issues and propose ideas to fix them. In the pilot phase students from 10 schools (including Edgard’s CED Casa Grande) participated in the process. In total, they identified over 600 issues including burnt out light bulbs, missing fire extinguishers and broken chairs. The students, as well as teachers, were also surveyed on the mode of transportation they use to go to school and their opinions about the school on a wide range of issues, ranging from the quality of educational materials provided to them to the state of the sports arena and labs. The CGDF compiled the issues identified and survey responses from each school into a report which detailed the audit findings which included images, descriptions and deadlines, which were then presented to the department of education. The Comptroller General visited each school later that year to monitor the results of the project and to oversee the resolution of the issues. In one school alone, the students identified 115 issues and within just 3 months, 45% of the issues were fixed either by the department of education or, where possible, by the students and school management themselves.[8]

Institutional Impact

The success of the project was two-fold. It not only enhanced the CGDF to conduct detailed audits of every public school but also generated greater buy-in from the schools to identify, report and fix issues in their surroundings. The buy-in from school management was a critical takeaway for the CGDF. By allowing the schools themselves to identify the issues, the CGDF was able to perform a full audit of the schools and see how public funds were spent without the negative connotation associated with being “overseen or audited.” Rather, the schools were able to see for themselves how misusing funds or neglecting the upkeep of school property was creating several issues for the students and teachers and the department of education was made aware of the most urgent issues public schools in Brazil were facing.

“This is the best way to fight against corruption. When the citizen understands that the public good belongs to him, he takes care of it” said Ziller. “Controladoria na Escola involves students in identifying and solving the institution's problems. This makes them aware, for example, that if they vandalize a bathroom, they lose resources that could be invested in improving the college.”

Expansion: The school audit award (2017)

The project’s great success was also evidenced by the fact that the social (also called civic) audit model was replicated the following year (2017), this time in 104 schools with over 4,000 students competing for a R$ 140,000 ($43,000 USD) grant award. It was called the “school audit award” and by the end of the campaign, students had submitted around 7,500 responses[9] to the survey.

In 2018, the program is set to expand to over 200 schools in the country.[10]

How it worked

The scale of participation in the first school audit award was much larger than the pilot. Hence, manually compiling reports from the data collected by the students was infeasible. Instead, the CGDF deployed Promise Tracker - a data collection tool developed by the MIT Center for Civic Media Promise Tracker is a mobile application which allows campaign organizers to create surveys for distribution in order to collect information in the form of pictures, text and location data.

The school audit award campaign consisted of 5 phases:[11]

- Training for teachers to guide students through the data collection process

- Theatrical shows and debates to show the value of citizenship and public participation

- Student-led evaluation of school infrastructure (using Promise Tracker)

- Student-led assessment of the problems identified

- Student-led development of solutions to fix them

Judges from the Comptroller General’s office scored each school based on its performance in each of the activities and the top 10 schools[12] shared the R$ 140,000 ($43,000) grant award.[13] Nearly 4,000 students from 104 public schools participated in the campaign and helped evaluate the state of classrooms, availability of Wi-Fi and computer labs, toilet paper in bathrooms and other issues by collecting evidence in response to a questionnaire administered through Promise Tracker.

Nearly 4,000 students from 104 public schools participated in the campaign and helped evaluate the state of classrooms, availability of Wi-Fi and computer labs, toilet paper in bathrooms and other issues by collecting evidence in response to a questionnaire administered through Promise Tracker.

Using the information they gathered, the students then went through a process to determine the root causes (such as student behavior, lack of resources and administrative issues) of the most commonly reported issues and went on to propose projects to address the issues they felt they could have an influence on.

By the end of the competition, all 104 schools had not only proposed but also implemented at least one - if not more - student-designed initiatives even though only the top 10 teams stood a chance to win the grant award.[14] Among other reasons, giving participants the ability to intervene in their local environments in order to affect real change was a critical factor in achieving such large-scale participation.[15]

Among the projects the students developed was the Monitoring My School app designed to monitor the cleanliness of classrooms and common areas. The app also allowed janitorial staff to provide feedback on how the students maintained the tidiness of the school. Another school launched a web-based radio station by renovating an old, out-of-use computer lab to motivate students and teachers to maintain the space well.[16]

Figure 1: The winners of the Civic audit received a certificate from the Comptroller-General, Henrique Ziller, Source: Andre Borges/Agência Brasília

Figure 1: The winners of the Civic audit received a certificate from the Comptroller-General, Henrique Ziller, Source: Andre Borges/Agência Brasília

Technology

The open source Promise Tracker Tool (URL: https://monitor.promisetracker.org/)[17]

How it works: Creating a campaign using Promise Tracker

Step 1: Describe Project: The tool asks the campaign organizer to describe the project and its targeted audience.

Step 2: Set up Survey: The tool then allows the organizer to create a survey which can be disseminated among the public for data collection. The organizer can ask users to respond with text, images and/or location information.

Step 3: Design Survey Page: Next, the organizer is asked to design the look and feel of the survey page. Once complete, the tool provides a QR code, a machine-readable code consisting of an array of black and white squares, used for storing URLs,, and links for sharing the survey with the public. If required, the organizer can choose to be anonymous.

Step 4: Test Survey: The organizer can test the final survey to make sure all the fields work as required prior to making it public.

Step 5: Collect Data: Once the survey is live, the organizer can view the results on a dashboard which visualizes the results, displaying graphs, maps and photos.

Figure 2: Promise Tracker Sample Dashboard. Source: monitor.promisetracker.org

Figure 2: Promise Tracker Sample Dashboard. Source: monitor.promisetracker.org

How it works: Responding to the survey

Step 1: Download Mobile App: After downloading the Promise Tracker mobile app, the user can download the campaign survey using a 6-digit code shared by the organizer.

Step 2: Data Collection: The type of data a user must collect depends on the requirement of the campaign. This might include text, images or location information.

Learnings

Design the initiative in a way that generates buy-in: Some schools were hesitant to take part in a campaign that was going to “monitor and audit” their activities. However, engaging students and teachers and giving them the power to create change persuaded schools that it would be a value-add to the school rather than become “monitoring” in a negative sense.

Technology is a small piece - focus on networks for engagement: Working with community groups on the ground who already have a certain network and issues they care about was critical to the success of the campaign. In this case, the comptroller-general

The civic audit model employed in Brazil is a great example of organizing citizen-led campaigns to foster civic education and to help government oversight agencies understand local issues in granular detail. It also helps build a sense of community and, when done right, motivates citizens to take action to fix those issues. It is still unclear, however, if the campaign improved educational outcomes and if the medium and long-term solutions were implemented.

It is important to ensure that issues reported by citizens are used to enhance government accountability and improve policy implementation and formulation. If citizens don’t see that the data they collect is being acted on, they are less likely to participate in subsequent iterations of the project. On the other hand, government can take action only if the information from citizens is routed to the appropriate departments. For instance, reporting a leaky roof in a school to the department of education is likely to be less impactful and slower (or entirely useless) if the relevant authority to fix the issue is actually the public works department. In other words, there needs to be a feedback loop which carries citizen input to the relevant authority and one that informs the citizen when their report has been acted upon.

An interesting example of a platform which attempts to do this comes from Ghana and a platform called TransGov Ghana.

TransGov Ghana

Background

Created in 2014, TransGov is a platform to help Ghanaian citizens monitor the progress of local development projects.[18] The creators of TransGov (Jerry Akanyi-King, Kennedy Anyinatoe, Kwame Yeboah and Prince Anim) found that citizens were unaware of whom to hold accountable for faulty or incomplete infrastructure projects (such as the construction of public schools and flyovers) and service delivery in their localities. The solution they developed was “to curate a list of development projects in local communities and give people the ability to comment, give feedback and let their voices be heard.”[19] The platform also allows people to report issues such as burst pipelines or potholes and track the status of their complaint. Today, TransGov has 600,000 registered users[20] who can provide feedback through the TransGov website, mobile app, by SMS or by phone. The platform is run by a small team of 6 employees who handle the technology, management and communications of the project.

Problem it solves

In Ghana, there are no official mechanisms to allow citizens to easily find details of local infrastructure projects. For over four years now, the Ghanaian parliament has deliberated on the passage of a right to Information bill but it is unclear when it will materialize. Ghana is part of the Open Government Partnership (OGP) and puts out open data on the national open data portal (data.gov.gh). But even the portal boasts of “133 datasets”, only 15 datasets (mostly census data) are available to view or download and they are rarely updated. Infact, the OGP end-of-term review report in 2017 found[21] that Ghana had made “limited” progress in its commitment to make datasets publicly accessible on the portal. Without a right to information bill or a robust open data portal, Ghanaian citizens have to resort to speaking with the government officials in the relevant departments and requesting information from them.

This poses two challenges: 1) It is often unclear which government authority is responsible for executing a certain project; and 2) Citizens have to find the individual within the department who is responsible for the project or any related information. This lack of clarity and accountability often means that citizens’ complaints or requests for information remain unresolved and increase their apathy towards government.”

“This lack of clarity and accountability often means that citizens’ complaints or requests for information remain unresolved and increase their apathy towards government.”

Prince Anim, Co-founder, TransGov Ghana

How it works:

TransGov serves two purposes: 1) Tracking the progress of public projects and sharing relevant details with citizens; and 2) Serving as a platform for citizens to report faults in service delivery (like broken pipes or potholes) and directing those complaints to the competent authority.

- Monitoring the progress of public projects: TransGov provides a snapshot of important information related to local infrastructure projects. This information includes details like proposed completion dates, funding, contractor information and current status. The fields are populated by a combination of crowdsourced data collection (where users submit pictures and comment on the status of the project) and curated data collection from official sources and interviews with contractors and officials. TransGov also shares this data with Ghana’s national open data portal.[22]

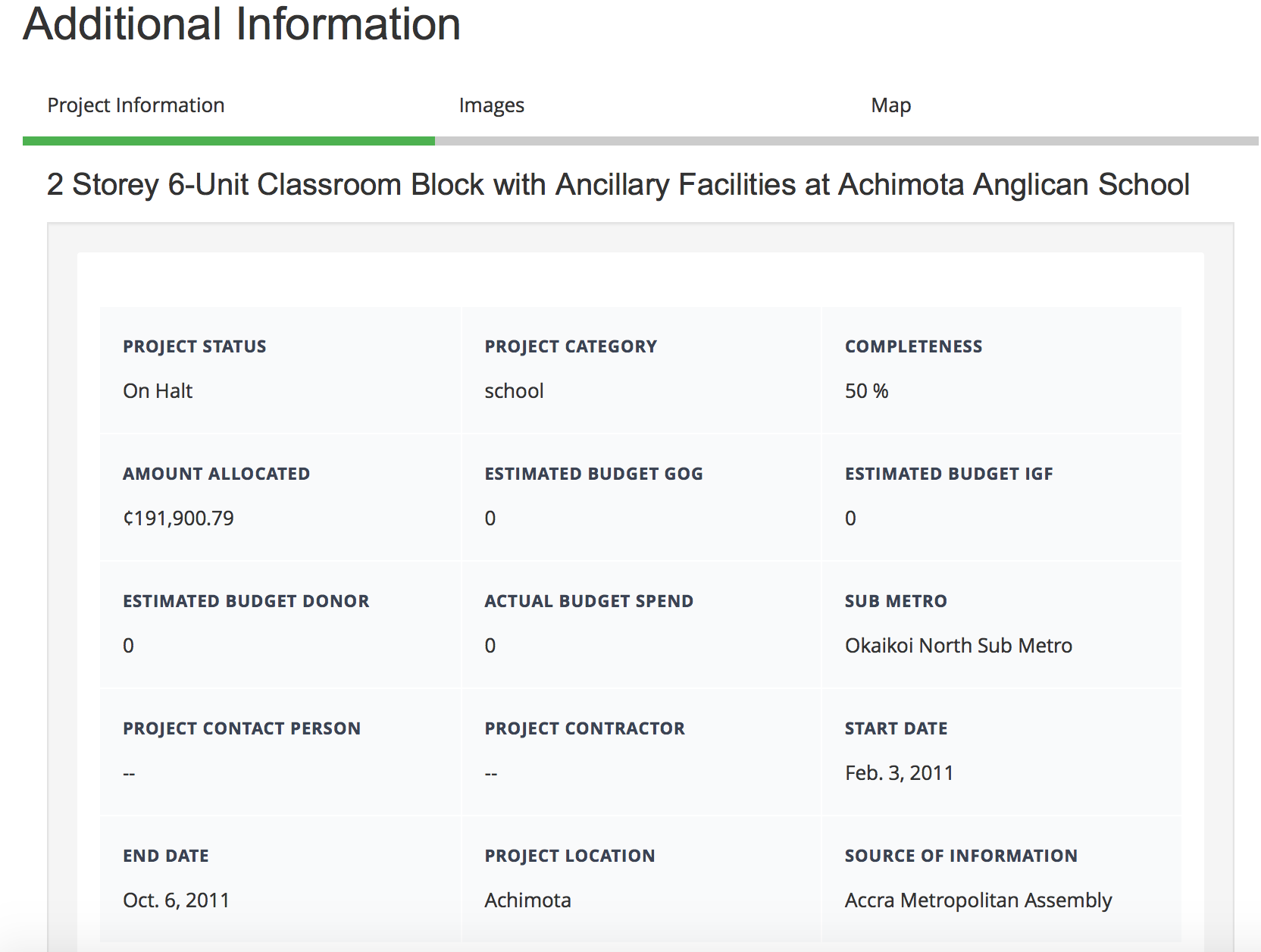

Figure 3: Sample project on TransGov Ghana. Source: http://transgovgh.org

- Reporting complaints: A registered user can post a complaint (including pictures and videos) on TransGov through the web platform or using the mobile app. The complaints are forwarded to the relevant department where officials view the complaints on a dashboard and take action. The department updates the status of the complaint when it is resolved and a notification is sent to the complainant to confirm if it was indeed resolved. To streamline the flow of information to government departments, every complaint is “tagged” and every department’s dashboard only displays the complaints tagged to them.

Institutional support:

The TransGov team’s first challenge was to identify individuals within government departments who had the vision to support TransGov’s efforts. In association with partners like the World Bank office in Ghana, Prince Amin and his team carried out a “power mapping” to strategically find the individuals and departments to work with and then narrowed down their focus to three government departments: 1) The ministry of finance; 2) The ministry of roads and housing; and 3) The Ghana water agency. While they work in tandem with these agencies, there is no dedicated unit or staff within government to deal with the complaints received through TransGov.

Communications strategy:

The second challenge was to inform citizens about TransGov and how it could be used. The team used a combination of online and offline engagement strategies to build the initial user base of TransGov. For example, the team used Facebook ads to spread the word online and laid the groundwork for further promotions. They also organized townhall meetings (often in the presence of local district heads) to educate people about their rights and to demonstrate the platform’s functioning. “A large part of the initial registrations for TransGov came through word of mouth advertising from friends and followers.”

“A large part of the initial registrations for TransGov came through word of mouth advertising from friends and followers.”

Prince Anim, Co-Founder, TransGov Ghana

Impact:

Overcoming people’s apathy and fostering participation was a big challenge for the TransGov team as was getting government to respond more quickly. But TransGov’s success, according to Prince Anim, should be measured by two metrics: 1) Number of issues it resolves; and 2) The timeframe of responses to complaints. TransGov serves as a conduit between citizens and the concerned department. This helps improve interactions between the two but does little to improve the process or pace of resolving the actual complaint. TransGov has taken steps to improve that aspect as well. By posting complaints received on TransGov to social media sites, the time taken to resolve complaints reduced by nearly 60% since public officials were subjected to the heightened scrutiny. On average it takes 3 days to fix a pothole and 48 hours to fix a burst pipe reported via TransGov compared with nearly a week to fix a pothole and more than 3 days to fix a pipe before TransGov’s social auditing process. There is still plenty of room for improvement.

Connecticut Policy and Economic Council (CPEC): City Scan

Background

Created in 2014, TransGov is a platform to help Ghanaian citizens monitor the progress of local development projects.[18] The creators of TransGov (Jerry Akanyi-King, Kennedy Anyinatoe, Kwame Yeboah and Prince Anim) found that citizens were unaware of whom to hold accountable for faulty or incomplete infrastructure projects (such as the construction of public schools and flyovers) and service delivery in their localities. The solution they developed was “to curate a list of development projects in local communities and give people the ability to comment, give feedback and let their voices be heard.”[19] The platform also allows people to report issues such as burst pipelines or potholes and track the status of their complaint. Today, TransGov has 600,000 registered users[20] who can provide feedback through the TransGov website, mobile app, by SMS or by phone. The platform is run by a small team of 6 employees who handle the technology, management and communications of the project.

Problem it solves

In Ghana, there are no official mechanisms to allow citizens to easily find details of local infrastructure projects. For over four years now, the Ghanaian parliament has deliberated on the passage of a right to Information bill but it is unclear when it will materialize. Ghana is part of the Open Government Partnership (OGP) and puts out open data on the national open data portal (data.gov.gh). But even the portal boasts of “133 datasets”, only 15 datasets (mostly census data) are available to view or download and they are rarely updated. Infact, the OGP end-of-term review report in 2017 found[21] that Ghana had made “limited” progress in its commitment to make datasets publicly accessible on the portal. Without a right to information bill or a robust open data portal, Ghanaian citizens have to resort to speaking with the government officials in the relevant departments and requesting information from them.

This poses two challenges: 1) It is often unclear which government authority is responsible for executing a certain project; and 2) Citizens have to find the individual within the department who is responsible for the project or any related information. This lack of clarity and accountability often means that citizens’ complaints or requests for information remain unresolved and increase their apathy towards government.”

“This lack of clarity and accountability often means that citizens’ complaints or requests for information remain unresolved and increase their apathy towards government.”

Prince Anim, Co-founder, TransGov Ghana

How it works:

TransGov serves two purposes: 1) Tracking the progress of public projects and sharing relevant details with citizens; and 2) Serving as a platform for citizens to report faults in service delivery (like broken pipes or potholes) and directing those complaints to the competent authority.

- Monitoring the progress of public projects: TransGov provides a snapshot of important information related to local infrastructure projects. This information includes details like proposed completion dates, funding, contractor information and current status. The fields are populated by a combination of crowdsourced data collection (where users submit pictures and comment on the status of the project) and curated data collection from official sources and interviews with contractors and officials. TransGov also shares this data with Ghana’s national open data portal.[22]

Figure 3: Sample project on TransGov Ghana. Source: http://transgovgh.org

- Reporting complaints: A registered user can post a complaint (including pictures and videos) on TransGov through the web platform or using the mobile app. The complaints are forwarded to the relevant department where officials view the complaints on a dashboard and take action. The department updates the status of the complaint when it is resolved and a notification is sent to the complainant to confirm if it was indeed resolved. To streamline the flow of information to government departments, every complaint is “tagged” and every department’s dashboard only displays the complaints tagged to them.

Institutional support:

The TransGov team’s first challenge was to identify individuals within government departments who had the vision to support TransGov’s efforts. In association with partners like the World Bank office in Ghana, Prince Amin and his team carried out a “power mapping” to strategically find the individuals and departments to work with and then narrowed down their focus to three government departments: 1) The ministry of finance; 2) The ministry of roads and housing; and 3) The Ghana water agency. While they work in tandem with these agencies, there is no dedicated unit or staff within government to deal with the complaints received through TransGov.

Communications strategy:

The second challenge was to inform citizens about TransGov and how it could be used. The team used a combination of online and offline engagement strategies to build the initial user base of TransGov. For example, the team used Facebook ads to spread the word online and laid the groundwork for further promotions. They also organized townhall meetings (often in the presence of local district heads) to educate people about their rights and to demonstrate the platform’s functioning. “A large part of the initial registrations for TransGov came through word of mouth advertising from friends and followers.”

“A large part of the initial registrations for TransGov came through word of mouth advertising from friends and followers.”

Prince Anim, Co-Founder, TransGov Ghana

Impact:

Overcoming people’s apathy and fostering participation was a big challenge for the TransGov team as was getting government to respond more quickly. But TransGov’s success, according to Prince Anim, should be measured by two metrics: 1) Number of issues it resolves; and 2) The timeframe of responses to complaints. TransGov serves as a conduit between citizens and the concerned department. This helps improve interactions between the two but does little to improve the process or pace of resolving the actual complaint. TransGov has taken steps to improve that aspect as well. By posting complaints received on TransGov to social media sites, the time taken to resolve complaints reduced by nearly 60% since public officials were subjected to the heightened scrutiny. On average it takes 3 days to fix a pothole and 48 hours to fix a burst pipe reported via TransGov compared with nearly a week to fix a pothole and more than 3 days to fix a pipe before TransGov’s social auditing process. There is still plenty of room for improvement.

Footnotes

[1] “The magenta book: Guidance for evaluation.” Her Majesty’s Treasury, April 2011.

[2] “Brief 1: Overview of Policy Evaluation.” Center for Disease Control, 2015.

[3] Special thanks to Prince Anim (co-founder, TransGov Ghana), Emilie Reiser (Project Director, Promise Tracker) and Eric Pettersen and Michael Meotti (CPEC) for their inputs.

[4] Claudio Ferez, Frederico Finan, and Diana Moreira. "Corrupting learning: Evidence from missing federal education funds in Brazil." Journal of Public Economics 96.9-10 (2012): 712-726.

[5] The office of the CGDF (Corregedoria-Geral do Distrito Federal) is responsible for overseeing public spending and plays the role of ombudsman in the federal district. “Publicação DODF nº 250.” Comptroller General of the Federal District, Dec. 27, 2002, Págs. 167/168

[6] “Projeto Controladoria Na Escola." Governo Do Distrito Federal, June 2016.

[8] Moll, Gabriella. “Horta comunitária será usada na merenda do CEF 404, em Samambaia.” Governo Do Distrito Federal, Nov. 7, 2016.

[9] Sarmento, Larissa. “Projeto Controladoria na Escola premia dez instituições de ensino do DF.” Governo Do Distrito Federal, Dec. 8, 2017.

[10] Sarmento, Larissa. “Projeto Controladoria na Escola inicia etapa de preparação para 2018”, Governo Do Distrito Federal, Feb. 8, 2018.

[11] Reiser, Emilie. “Civic Audit to launch in 100 schools in Brasília.” Promise Tracker, Aug. 22, 2017.

[12] Moreira, Cibele. “Controladoria-Geral do DF lança prêmio Escola de Atitude.” Governo Do Distrito Federal, Aug. 17, 2017.

[13] Moreira, Cibele. “Controladoria-Geral do DF lança prêmio Escola de Atitude.” Governo Do Distrito Federal, Aug. 17, 2017.

[14] Interview with Emilie Reiser, Project Lead, Promise Tracker on February 14, 2018

[15] Interview with Emilie Reiser, Project Lead, Promise Tracker on February 14, 2018

[16] Reiser, Emilie. “Students take Brasília.” Promise Tracker, Dec. 15, 2017.

[17] The Promise Tracker Tool is open source and is available at https://github.com/mitmedialab/Promise-Tracker-Builder

[19] Interview with Prince Anim, Co-founder, TransGov Ghana

[20] Approximately 40% active users. Active users: Users who, in the preceding month, engaged on the platform by reporting issues and retweeting or tagging posts.

[21] OGP End-of-Term report: Ghana, OGP 2017

[23] CityScan project case study, Michelle Doucette Cunningham available online at http://web.archive.org/web/20040620033401/http://www.city-scan.com:80/moreinfo/city_scan_case_study.pdf. Last accessed on June 18, 2018

[24] http://www.townofwindsorct.com/townmanager/tm-reports.php?report=100

[25] City-scan.com. Accessed through wayback machine on June 18, 2018

[26] Retrieved from http://www.city-scan.com:80/section.php?section=youth through wayback machine at http://web.archive.org/web/20040229111921/http://www.city-scan.com:80/section.php?section=youth on June 18, 2018

[27]CityScan project case study, Michelle Doucette Cunningham available online at http://web.archive.org/web/20040620033401/http://www.city-scan.com:80/moreinfo/city_scan_case_study.pdf. Last accessed on June 18, 2018

[28] CityScan project case study, Michelle Doucette Cunningham available online at http://web.archive.org/web/20040620033401/http://www.city-scan.com:80/moreinfo/city_scan_case_study.pdf. Last accessed on June 18, 2018