vTaiwan

Using Digital Technology to Write Digital Laws

Read Time

Brief View 6 MINS

Full Story 18 MINS

Briefing Notes

How Does It Work?

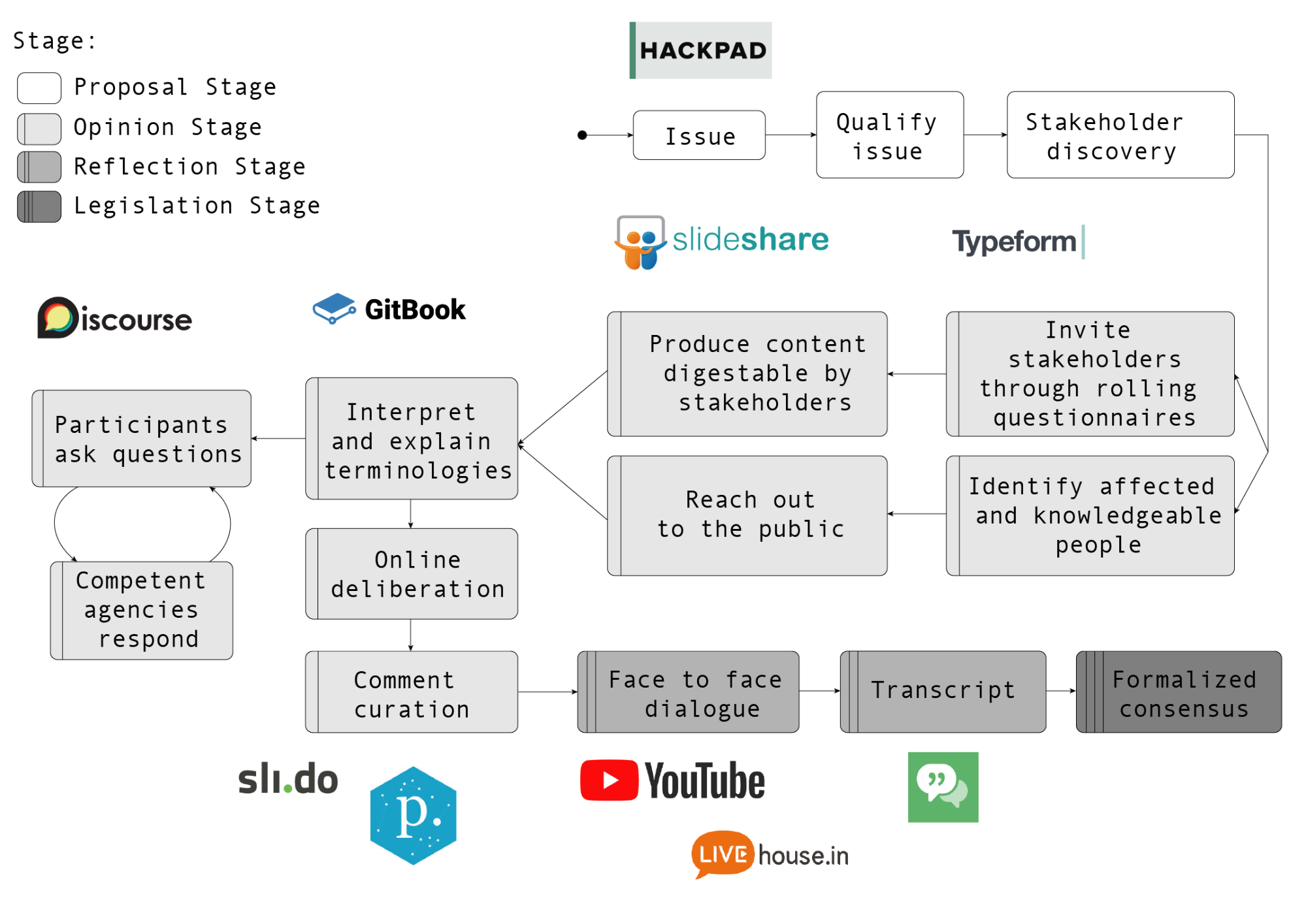

vTaiwan is a four-stage online and offline process for moving from issue to legislative enactment while building consensus among diverse stakeholders. It has been used to craft 26 pieces of legislation relating to the digital economy collaboratively between the government and the public. vTaiwan relies on a series of existing open source tools (meaning they can be freely modified and customized, as needed). The process begins with a member of the public proposing an issue and a relevant government agency agreeing to steward and participate in the process. Since 2017, each Ministry is obliged to appoint a Participation Officer responsible for engaging in the process.

- Proposal Stage - Offline and online discussion of which problems to address using Discourse for discussion, sli.do for document sharing and Typeform for frequent questionnaires.

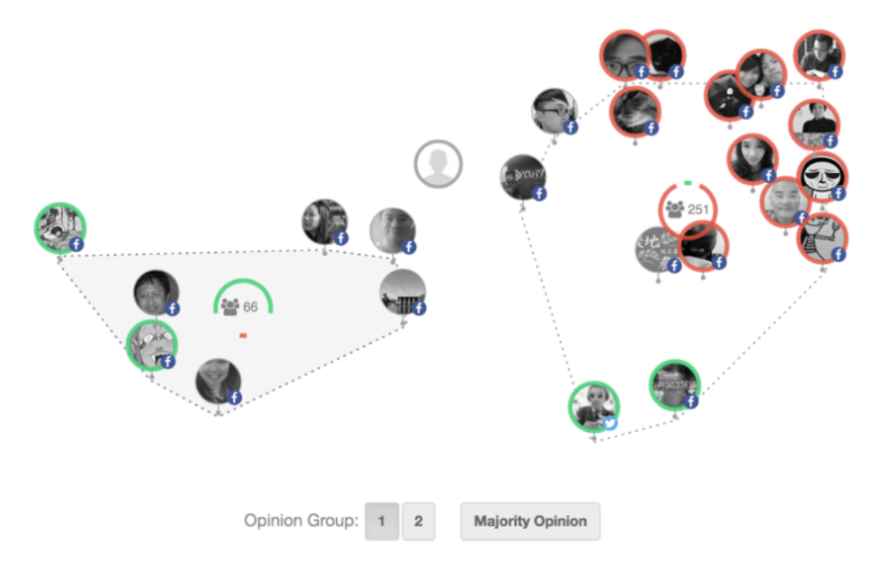

- Opinion Stage- Discussion then moves to an online process of getting input, taking advantage of an artificial intelligence (AI) tool known as Pol.is to collect and visualize participants’ views, which becomes the basis for determining the extent of consensus about the nature of a problem. During this stage participants post their statements about the problem and can vote to Agree, Disagree or Pass on statements written by others or indicate if the statement is important to them. As voting progresses an algorithm is used to sort participants into opinion groups, capturing what each group feels most strongly about, how a group perceives what the problems are and areas where people are divided and where there is consensus. Presented as a visualization, this “opinion landscape” is made available to the public and the relevant government agencies. This so-called “crowdsourced consensus-mining” makes the process of obtaining information about the “dynamics of the issue, the facts of the matter, what is at stake, and who is involved” efficient and scalable.

- Reflection Stage - Following the opinion stage are two in-person stakeholder meetings where notes are taken online using HackPa d and, to extend participation and maximize transparency, livestreamed online with a chatroom where anyone can comment. The goal is determine if the issue is ripe for advancement.

- Ratification Stage - In some cases, the issue is resolved with a guideline, policy, or statement from the competent government agency. This often includes a point-by-point explanation of why legislation is not being enacted. In others, it is formulated into a draft bill to be sent to the Yuan (Taiwanese Legislature).

All the steps are combined onto a single set of webpages on the vTaiwan website so that the public and public servants alike can easily track the progress of an issue. Taiwan’s Digital Minister stresses that the process is flexible and the path often deviates from this roadmap. Some issues have taken as few as three months to settle while others have taken over a year.

What are the outcomes?

In Taiwan, 200,000 people have participated in this open policymaking process to define the problem around such complex issues as Uber, telemedicine, online alcohol sales and other hard topics. More than 80% of processes once initiated lead to “decisive government action.” The Taiwanese have used the process to formulate 26 pieces of national legislation over the last five years.

What does it cost?

The vTaiwan process uses a number of different tools, most of which are free. Pol.is is free to use and also open source. The vTaiwan process was supported pro bono by the organization that develops and maintains pol.is, which provides support at negotiable fees. The entire process is run and maintained by volunteers with support from the government’s Digital Ministry. [a]

What are the benefits?

- Joint ownership between government and civil society builds trust and reduces the risk of failure while sharing workload.

- Flexible and transparent process enhances legitimacy.

- Combination of online and offline fosters participation by diverse audiences,

What are the risks?

- Focus on generating consensus may conflict with the need for urgent response.

- Not all Ministries or public officials are convinced of the efficacy of the process.

- Online process tends to favor discussion of technology-related topics.

vTaiwan has facilitated productive discourse among thousands of people at a time on a range of key issues. The process has helped resolve disputes between groups, ease concerns among citizens, and ultimately shape more effective and representative policies.

Correction

An earlier version of this case study had an incorrect description of the cost structure for using pol.is. That information has been updated with the input of Pol.is.[October 14, 2020]

Introduction

For three weeks in April 2014, students, academics, and everyday citizens piled into the Taiwanese Parliament in Taipei to protest the passage of the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement aimed at liberalizing trade with China. The government negotiated the Agreement behind closed doors giving rise to protests now known as the Sunflower Movement. g0v.tw, the largest civic tech community in Taiwan--which was founded to promote government transparency and the use of tools to enable citizen participation-- led the protests.

The Taiwanese government responded to the demonstration by acknowledging the public’s peaceful demands. In turn, former Taiwanese Minister without Portfolio Jaclyn Tsai attended a g0v.tw hackathon in December 2014 and asked the volunteers if they could “create a platform for rational discussion and deliberation of policy issues that the entire nation could participate in.”[1] If they were up to the challenge, Tsai committed that the government would participate and respond.Shortly after, the g0v.tw volunteers built vTaiwan: an open consultation process to bring together experts, government officials, and relevant citizens on a national scale to deliberate, reach consensus, and craft legislation.

Shortly thereafter, the g0v.tw volunteers built vTaiwan: the open consultation process to bring together experts, government officials, and relevant citizens on a national scale to deliberate, reach consensus, and craft legislation.[2]

vTaiwan has since transformed into a systematic online and offline process to reach consensus on large-scale issues and craft national legislation, helping lawmakers implement decisions with a greater degree of legitimacy. While this case focuses on vTaiwan’s influence on the problem identification stage, it is important to note that vTaiwan enables public participation in each step of the lawmaking process.

Mechanics / Workflow

At the time of vTaiwan’s inception, instead of g0v.tw ceding control of the program to the government, its inventors and stakeholders decided that vTaiwan should exist as a platform independent of government, run collaboratively between civil society and the public sector. vTaiwan was founded with the agreement that the government will use the opinions gathered throughout the process to shape legislation on any given issue related to the digital economy. Now, three parties are in charge of its operations:[3]

- Issue sponsors: the government agencies which submit drafts of laws and regulations that they are proposing.

- Editors: individuals affiliated with the Science & Technology Law Institute, a government-sponsored NGO, who collect and organize the drafts into a format more conducive to discussion.

- Administrators: g0v's vTaiwan task force, which works together to maintain the online system and update the content.

Although vTaiwan is government-funded, because volunteers run the process, it enjoys a relatively high degree of legitimacy.

The process comprises four distinct phases: proposal, opinion, reflection and legislation.

The platform’s administrators, however, stress that the system is flexible and the path of an idea often deviates from the ideal type depicted in this roadmap.[4] Some issues have taken as few as three months to settle while others have taken more than a year.

Figure 1: Image copied from https://info.vtaiwan.tw/

The vTaiwan Process

- Proposal Stage

- Diverse people including programmers, developers, public servants, journalists, scholars, legal specialists, and students convene both online or offline for a weekly mini-hackathon hosted by vTaiwan every Wednesday.[5]

- At these mini hackathons, contributors propose an issue of their choosing to a “competent government authority”[6] who may choose to either accept (thereby becoming accountable for the issue) or refuse to take on the topic of the proposal. Notably, a proposed issue will not initiate the vTaiwan process without a government authority agreeing to become accountable for it, and a facilitator taking charge of the issue.

- The facilitator must be present to guide the issue through each stage of the process. He/she uses a “Focused Conversation Method” to lead discussion throughout each stage. This method is summarized as follows:

- Objective - participants share facts and data (e.g., vTaiwan is a project)

- Reflective - participants express their emotions and feelings about the objective facts (e.g., I think vTaiwan is a great project and here’s why)

- Interpretive - participants exchange opinions and values (e.g., vTaiwan is a project that should expand)

- Decisional - participants make decisions and reach consensus (e.g., we concluded that vTaiwan expands within a month)

- Tools - during the proposal stage, notes taken during mini hackathons are shared using a collaborative notetaking tool (Hackpad), while documents and presentations are shared using SlideShare.

- Stakeholder Identification - The community[7] researches and identifies relevant stakeholders. In this case study, stakeholders are defined as any person or group affected by and/or has knowledge about the given issue.

- Opinion Stage - Public opinion regarding the issue is gathered through several methods as the issue gets further refined.

- The vTaiwan community launches the opinion collection process and produces a description of the case in a form digestible by stakeholders and the general public. This includes publishing any documents, research and/or presentations relevant to the proposal. If there is terminology that is difficult to understand, it is compiled into an open dictionary, where everyone can contribute to make things clearer.

- “Rolling Questionnaires” - first, in an effort to keep the ball rolling and collect as many valuable opinions as possible, stakeholders within the community’s network are sent questionnaires which ask what they know about the issue and their experiences with it. Notably, stakeholders are also asked if they can recommend others with knowledge and/or experience relevant to the issue. Subsequently, other individuals are sent the same survey, often via online advertisements and Facebook. Several actions are taken to maintain privacy but also to enhance the opinion collection process and augment the crowd that is surveyed.

- The respondent has the option to either keep their responses confidential within the vTaiwan community or publish his/her opinions publicly.

- Either way, the respondent has the option to remain anonymous.

- The respondent is also asked whether they would like to undergo a more in-depth interview.

- The respondent is given the option to subscribe to email updates regarding the issue.

- The vTaiwan community creates an online forum on which anyone, not restricted to Taiwan residents, can ask questions, comment on ideas or choose to “agree,” “disagree” or “pass” on others’ ideas, and that forum is open for a designated period of time. Each round of opinion collection lasts for at least one month, but there is no limit to the number of rounds.

- In order to foster consensus building, however, the process then calls for using Discourse (discussion tool) and Pol.is (opinion mapping).

- Discourse is a discussion platform which allows users to tag competent authorities, who, in turn, are obliged to respond to comments within seven days.

- Pol.is is an opinion mapping tool to help a large group build consensus by helping the group to visualize its own opinions.

- The Pol.problem definition process with the public unfolds in multiple phases. In the first round, organizers, followed by participants, write statements about the problem. In other words, the organizers create sample problem statements to prompt discussion.

- In the second round, participants are asked to ‘Agree,’ ‘Disagree’ or ‘Pass’ on those statements or answer “Is This Statement Important to You.”

- Statements are shown to all participants based on a comment routing system that gives each statement a priority score based on the responses it has received so far. Every person who enters the conversation sees a different ordering of the statements to avoid bias. As voting progresses, the algorithm then finds the underlying structure of the conversation using unsupervised machine learning. The software analyzes the votes and visualizes them in a real-time report known as an opinion landscape.

- Through multiple rounds of the process, it becomes easier to see where there is consensus or disagreement and by whom.

- Once the opinion process is closed, all interactions are reviewed, analyzed, and curated by the vTaiwan community. They are used to publish two reports (“raw and second-hand”)[8] on the results of the opinion collection stage that are viewable by the public and also submitted to the relevant government authority. The reports are used as materials to set the agenda and as a topic of discussion for the upcoming mini-hackathon and consultation meeting.

- Reflection - a shorter stage comprised of two face-to-face events to reflect on findings thus far and determine if it is time to proceed or undergo another round of opinion collection.

- If the competent authority and the g0v.tw participants conclude that it is time to proceed, then they design an in-person consultation and:

- Identify the proper facilitator for the meeting.

- Define the size and scope of the issue with the competent government agency.

- Host a pre-meeting with the facilitator and competent authority at least one week prior to the consultation meeting.

- Create a plan for the meeting, which includes a rundown, an agenda, a list of invited guests and participants, and other logistical details.

Figure 2: Example of Pol.is opinion groups being formed[9]

Then, the in-person consultation meeting is held, which invites key stakeholders, including scholars, public servants, private sector representatives and participants who were deemed highly active during the earlier stages, are invited. Although an invitation is required to participate in-person,the consultation meeting islivestreamed online via YouTube with a chatroom where anyone can contribute ideas, so that everyone can be involved even if they cannot physically attend. The facilitator decides which contributions from the chat to incorporate into the meeting, choosing “insightful and valuable opinions” to include. The meeting is also recorded and transcribed to be used as materials for the next action. The meeting begins with the facilitator describing a summary of the issue’s process thus far. Then, stakeholder groups are allowed to give presentations. During this process, the facilitator takes notes digitally to document a summary in real-time, which is all displayed on the projector. Following the meeting, the videos are released on the vTaiwan Facebook page so that citizens can continue to share ideas in the following weeks.

- Ratification - a final discussion on the results of the process which decides the action that the government will take.

- After the consultation meeting, there is another discussion between the community and competent government agency on:

- The raw report(s) from the opinion collection stage.

- The secondary study on the discussion throughout the vTaiwan process.

- The transcript of the consultation meeting.

- The “rough consensus”[10] → the relevant government agency is responsible for using this to take action.

- The final outcomes can take one of two forms:[11]

- In some cases, the issue is resolved with a guideline, policy, or statement from the competent government agency. This often includes a point-by-point explanation of why legislation is not being enacted.

- In others, the issue is formulated into a draft bill to be sent to the Yuan (Taiwanese Legislature).

Permanent Beta

Minister Audrey Tang emphasizes the importance of seeing the process as an experiment that can and will always be improved upon and modified . She explained that: “vTaiwan’s scope is not limited to Taiwan or any particular government; it’s an experiment to prototype a model for consensus generation among large groups in general.”

“vTaiwan’s scope is not limited to Taiwan or any particular government; it’s an experiment to prototype a model for consensus generation among large groups in general.”

Audrey Tang, Digital Minister, Taiwan

Moreover, she described it as, “an experiment for a new way of working together, to unconditionally trust when collaborating, to be more open and transparent, and to gain the potential to be trusted.”

The process is inherently adaptive, meaning each issue discussed through vTaiwan may follow a different path. No two issues are assumed to be identical in nature and there is scope for each issue to be subject to a unique process, with progress determined by the community involved. In some cases, all four stages are not required. For example, in the case of developing a Fintech Sandbox, an effort to liberalize regulation and allow innovative financial technology companies to thrive, the reflection stage was skipped because there was pressure for immediate legislation. Similar regulatory sandboxes for electric scooter usage, autonomous vehicles, and the 5G spectrum network are currently in development on vTaiwan.

There is no set policy in place to decide when an issue advances from one stage to the next. Rather, the vTaiwan community decides this when they reach a “rough consensus” at any given point in the process, based on the situation at the time. According to PDIS Co-founder Shu-Yang Lin, “every case is different, and should be treated differently.””[12]

Rather than aspiring to become a “best practice” for citizen engagement, vTaiwan’s stated goal is to advance knowledge and research in the field of digital and participatory democracy, so that other governments and institutions--including its own--may learn from it.

Participation

Since the platform’s launch in 2015, over 80 percent of vTaiwan deliberations have led to decisive government action.[13] One of the most notable processes, and the first to utilize the Polis software, was a 2015 debate over the country’s policies regarding taxis and the ride-hailing app Uber. Participation statistics from this process were as follows:

- 31,115 total votes (highest of any process to date)

- 145 statements submitted on Polis survey (during opinion gathering stage)

- 925 participants voted on Polis survey (opinion stage)

- 1,875 participants joined online during the two-hour live-streamed consultation meeting[14]

- 4,000+ participants crowdsourced the meeting agenda for the consultation

Key Learnings

vTaiwan offers a replicable, open-source model for supporting constructive collaboration between committed members of the public and public servants and suggests several lessons.

Keeping it user-friendly

Although vTaiwan includes multiple stages and different tools, each component is simple and easy to understand.[18] During a presentation she gave in Paris,Audrey Tang jokingly remarked that g0v is “a movement that tries everything [sic] to create a way for lazy people to engage in real action.” From using titles that are very slight offshoots of common existing references (gov→g0v, Taiwan→vTaiwan) to creating timelines to help participants understand the context of certain issues, vTaiwan makes every attempt to make their process simple and inclusive for everyone.

Engaging diverse audiences

With 85% of Taiwan’s population online and 90% on Facebook,[19] creating an online participation program was not a big stretch. What is unique is fostering a process to bring together different groups of people who do not usually work together, including tech experts, social activists, and public servants.

What is unique is fostering a process to bring together different groups of people who do not usually work together, including tech experts, social activists, and public servants.

Theg0v.tw and civic technology community have played an active role in developing new platforms for civic engagement beyond vTaiwan. One example is the civic engagement platform Join, which like vTaiwan uses Pol.is to build consensus, but is maintained by the government and aims to tackle regulatory topics beyond the digital economy. The Join platform has seen more than 10 million unique visitors since launching in 2015.

Figure 3: Interface of the Join platform

Another example is the crowdsourcing platform created by the vTaiwan community to fact-check the statements made by presidential candidates during public speeches in the lead-up to Taiwan’s 2020 election.g0v.tw even helped launch Talk to Taiwan,a sibling project of vTaiwan consisting of a broadcast talk show where government ministers, mayors and scholars show up to respond to citizen ideas and concerns expressed via Polis.

As Minister Tang said, “...I think [vTaiwan] is closer to the civic tech community than it is actually to my office or any minister...what we’re doing is institutionalizing the parts that worked.” Nonetheless, the vTaiwan community has made some efforts to institutionalize the process in law. One piece of legislation, a clause in the Digital Communications Acts, would have created a legal framework for the executive branch to respond to cross-ministerial issues that originated on forums like vTaiwan. However, this legislation, itself a product of vTaiwan, did not complete its parliamentary process in 2019. Regardless, there appears to be bipartisan support to create a dedicated authority to institutionalize digital policymaking processes like vTaiwan.

Mandating engagement

vTaiwan’s organizers have emphasized the importance of trust between citizens, civil society, and the public sector.[20] The government trusts activists to maintain this largely volunteer-run process, while the community activists trust the government to listen and use their insights and opinions to shape legislation. Building upon its initial commitment to use the platform, the additional requirement that began in 2017--that every ministry within the Taiwanese government assign at least one “participation officer” (PO) to “be involved in engagements with the civil society and to acquaint themselves with multi-stakeholder collaborative settings, as to shape regulations appropriate to their ministry”--is a crucial development.[21] Although many public officials are still reluctant participants, mandatory public engagement is beginning to create a culture of mutual trust.

Special thanks for editorial assistance to:

Fang-Jui Chang, Service Designer, PDIS Taiwan

Audrey Tang, Digital Minister, Taiwan

Impact

The Taiwanese government shifted from making decisions that angered the neglected public[15] to requiring each Ministry to create a vTaiwan forum account and holding them responsible for responding to citizens’ comments within seven days, resulting in a diverse range of topics being discussed on the platform, none of which are trivial. Although it tends to attract participants who often spur discussion on topics related to economics, data, and technology, vTaiwan has also exhibited its capacity to catalyze deliberation on issues of social justice such as the Nonconsensual Pornography case.

This award-winning platform has been praised for its innovation, impressive technology, and its ability to bridge the gap between online and offline participation, as well as gaps between various sectors and citizens. From topics like the sharing economy to security management, vTaiwan continues to showcase its capacity to invite stakeholders of all backgrounds to identify problems and generate rational, collaborative, and productive dialogue about key issues, to the point where possible solutions are often put forth and agreed upon.

Overall, it has proven to be a multipurpose platform that can help all parties that wish to be involved. It enables Taiwanese citizens to bring their concerns to light in a manner where they can actually be heard, while also diminishing the burden placed on lawmakers and public servants by fostering open, productive collaboration and mitigating citizen opposition.

The UberX case is touted as one of the most constructive processes facilitated through vTaiwan to date. Before the vTaiwan consultation, the regulation of ride sharing was a contentious topic.[16] Citizens were concerned for their safety as UberX did not require its drivers to obtain a professional driver’s license and was not subject to the same requirements as taxis. Taiwan’s taxi drivers complained that they were losing a significant portion of their business, hurting their income by 30 percent, according to Chen Deng, Chairman of the Taipei City Taxi Passenger Transport Trade Association. [17]

But, as a result of the vTaiwan process, Taiwan’s Ministry of Transportation and Communications pledged to ratify the consensus reached on Polis and amend the existing regulation consistent with the plans worked out online and agreed upon by Uber Inc., the Association of Taxi Drivers in Taipei, Taiwan Taxi, and the Ministries of Transport and Communications, Economic Affairs, and Finance. These included such changes as:

- Taxis no longer need to be painted yellow.

- High-end app-based Taxis are free to operate as long as they do not undercut the existing taxi fare.

- App-based dispatch systems must display car and driver identification, estimated fare, and customer rating.

- Per-ride taxation would be imposed.

The Uber case is evidence for the claim that the vTaiwan process does more than merely collect opinions; it provides a method for genuinely improving legislation.

Footnotes

- Barry, Liz. “Vtaiwan: Public Participation Methods On The Cyberpunk Frontier Of Democracy.” Civic Hall, 2016).

- Lin, Shu-Yang. “vTaiwan”, 2018.

- “Opportunities and Challenges in Digital Democracy: Taiwan 2014 > 2016 Open Government Report.” Open Culture Foundation, 2017.

- Oiticica, Ciro Brito. “Pol.is.” Participedia, 2016.

- Yu-Tang Hsiao, Shu-Yang Lin, Audrey Tang, Darshana Narayanan, Claudina Sarahe. “vTaiwan: An Empirical Study of Open Consultation Process in Taiwan.” Center for Open Science, 2018.

- Avross Hsiao. “vTaiwan Slide Deck.” 2018.

- Berman, Paula. “Hacking ideology: pol.is and vTaiwan.” Democracy Earth, 2017.

- Lin, Shu-Yang. “Reinventing democracy.” issu, Nov. 14, 2017.

- Tang, Audrey. “Uber responds to vTaiwan’s coherent blended volition.” Pol.is blog, May 23, 2016.

- O’Flaherty, Kate. “Taiwan’s revolutionary hackers are forking the government.” Wired, May 4, 2018.

- Jackman, Molly. “ALEC’s Influence over Lawmaking in State Legislatures.” The Brookings Institution, Dec. 6, 2013.

- Rashbrooke, Max. How Taiwan is inoculating itself against the Uber “virus.”, CityMetric, Feb. 8, 2017.

- Sui, Cindy. “Taiwan: The place Uber couldn't crack.” BBC News, Feb. 10, 2017.

- “2016-03-02 Conference at SuperPublic.” PDIS, Mar. 3, 2016.

- Rivière, Pauline. “What Makes a Good Online Citizen Participation Tool?” Citizenlab, Apr. 16, 2018.

- Atlee, Tom. “vTaiwan (Part 2) – Notes on Aspects of the vTaiwan Phenomenon.” Apr. 23, 2018.

- “Conférence Audrey Tang.” 27eregion, Mar. 8, 2016.

- Chris Wang, Lee Hsin-fang and Kan Chih-chi. “Protest gathers broad support.” Taipei Times, Mar. 31, 2014.

- Report. Pol.is, 2016.

- “Several economic laws and regulations to adjust online counseling meetings - spreading my personal privacy images in violation of my wishes." Executive Yuan, Sep. 14, 2017.

- “Legislative Yuan.” (2010).

- “Financial Supervision Sandbox.” vTaiwan, Dec. 29, 2017.

- Lee, MG and Wytze, Aaron. “vTaiwan Wins Big at the 2018 Interaction Awards.” g0v news, Feb. 21, 2018.

- “sharing economy.” vTaiwan, 2017.

- “security management.” vTaiwan, 2015.

- “Spread my own private image in violation of my wishes, vTaiwan.” vTaiwan, 2017.

Interviews:

Shu-Yang Lin (March 1, 2018)

Avross Hsiao (August 2, 2018)

[a]Colin Megill, Co-creater, Pol.is, via email October 14, 2020

[1] Barry, Liz. “Vtaiwan: Public Participation Methods On The Cyberpunk Frontier Of Democracy.” Civic Hall, 2016).

[3] “Opportunities and Challenges in Digital Democracy: Taiwan 2014 > 2016 Open Government Report.” Open Culture Foundation, 2017.

[4] Private presentation from and interview with Shu-Yang Lin, co-founder, PDIS Taiwan, March 1, 2018.

[5] Yu-Tang Hsiao, Shu-Yang Lin, Audrey Tang, Darshana Narayanan, Claudina Sarahe. “vTaiwan: An Empirical Study of Open Consultation Process in Taiwan.” Center for Open Science, 2018.

[6] “Competent authority” is a term used frequently in vTaiwan’s process materials. It simply refers to the relevant government agency that is legally responsible for handling a given issue (such as the Ministry of Health and Welfare). In this study, the phrase will be used interchangeably with phrases like “relevant government agency.”

[7] “Community” in this context is referring to the whole of the vTaiwan community

[8] The “raw” report includes the meta-data, numbers, statistics, etc. produced, whereas the “second-hand” report is an interpretation of that data.

[9] Berman, Paula. “Hacking ideology: pol.is and vTaiwan.” Democracy Earth, 2017.

[10] “Rough consensus” is a term used to describe the acknowledgement that it is unrealistic to try and reach a complete and perfect consensus within the entire population. The rough consensus refers to the idea/outcome that is deemed suitable for the highest proportion of the total stakeholders.

[11] Avross Hsiao. “vTaiwan Slide Deck.” 2018.

[12] Lin, Shu-Yang. “Reinventing democracy.” issu, Nov. 14, 2017.

[13] Avross Hsiao. “vTaiwan Slide Deck.” 2018.

[14] Tang, Audrey. “Uber responds to vTaiwan’s coherent blended volition.” Pol.is blog, May 23, 2016.

[15] O’Flaherty, Kate. “Taiwan’s revolutionary hackers are forking the government.” Wired, May 4, 2018.

[16] Rashbrooke, Max. How Taiwan is inoculating itself against the Uber “virus.”, CityMetric, Feb. 8, 2017.

[17] Sui, Cindy. “Taiwan: The place Uber couldn't crack.” BBC News, Feb. 10, 2017.

[18] “2016-03-02 Conference at SuperPublic.” PDIS, Mar. 3, 2016.

[19] “2016-03-02 Conference at SuperPublic.” PDIS, Mar. 3, 2016.

[20] Atlee, Tom. “vTaiwan (Part 2) – Notes on Aspects of the vTaiwan Phenomenon.” Apr. 23, 2018.

[21] Atlee, Tom. “vTaiwan (Part 2) – Notes on Aspects of the vTaiwan Phenomenon.” Apr. 23, 2018.